It’s no secret that air travel is a perishable service. A plane that flies half empty has many fixed costs like the aircraft itself, employees, IT systems, and airport facility fees. Reductions in variable costs like fuel are not enough to ensure the flight remains profitable, so it is imperative that the airline sell as many seats as possible. Sometimes this means lowering fares if there is limited demand on a certain route.

But how does one determine in advance if a decrease like this is on its way? The most common approach I hear people use is to look at the seat map. If half the seats are taken three weeks out, they assume the plane is under capacity and likely to see a fare reduction. But this logic is wrong for many reasons.

First, available tickets and available seats do not match up one to one.

Many carriers don’t even allow you to select seats in advance. Southwest Airlines is a good example, but there are others like British Airways that want to charge you for the privilege. Other carriers allow free advance seat assignments but may restrict you to certain areas of the plane. Be careful not to fall for this.

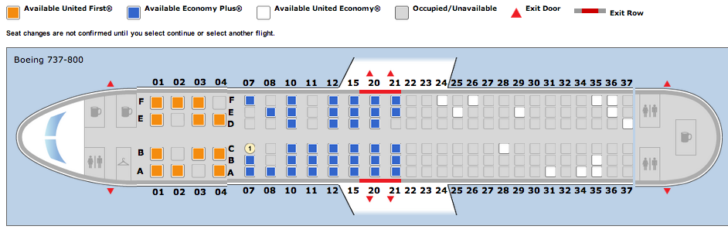

If you fly United Airlines and see that half the economy class cabin is empty, is it really empty or does it just happen to be the front half where EconomyPlus seats require an additional charge for non-elite passengers? American Airlines and several other carriers also have “preferred” seats in their economy class cabins. People might snap up the free seat assignments first and then latecomers give up and wait for an assignment when they check in. It doesn’t mean there are still 50 tickets for sale, only that 50 seats require an extra charge.

Second, many people don’t select a seat in advance.

I’m not just talking about our example with United and American. There are lots of passengers who just skip by the seat selection page when they purchase a ticket because they don’t care or for some other reason. The seat selection option may be on the receipt page, which people overlook, or it may require logging into the carrier’s website separately if you booked through another airline or travel agency. Even first class passengers may not select a seat.

Third, airlines regularly oversell their flights.

A certain number of people just don’t show up or cancel at the last minute. To keep planes full, airlines oversell their flights. They are actually pretty good at this. Extensive historical data helps them predict which flights, which days, and which times are most likely to accomodate additional passengers. If it’s Christmas Eve, they probably won’t sell too many extra, but other days may see five or more extras. When things go right, the plane still takes off full. When things go wrong, the airline must deny boarding to some passengers and pay them compensation.

Inventory management is an arcane art, but the lesson you should take away is that our original question only grazes the surface of the issue. I’ve already told you why the number of reserved seat assignments does not match the number of tickets sold. Now I’m telling you that the number of physical seats on the plane does not match the number of tickets available for sale in the first place.

Practical Solutions

Your best measure of unsold inventory is to look at the availability in each fare bucket. Fares are usually parceled out into a range of different prices with different restrictions. The total number may not add up to the number of seats on the plane, but if you see the lower fares start to disappear, that’s an indication that you might need to book soon.

Also check the actual fares and their rules. If you see a particularly cheap fare, find out when it expires and if there is an advance purchase restriction. These two things are separate. There may be no advance purchase restriction, but you have to buy it by June 30 even for travel next year. Other times, I’ve seen advance purchase requirements that are four months before travel. That far out, the plane was still pretty empty, but the day after four-month window the cheapest fare jumped from $800 to $1,100 for this international flight.

Those are both ways to avoid being stuck with more expensive fares, but they don’t really predict whether fares will go down in the future. For that, you can try looking at competition on the route. When a new carrier enters a market, prices usually drop as customers have more options. Look for announcements of upcoming changes (the airport authority may list these on its website to promote a new route or carrier). Or if aircraft are changed by existing carriers, there may be a drastic change in capacity. I saw one route I was flying on recently swap in a Dash-8 to replace an A319.

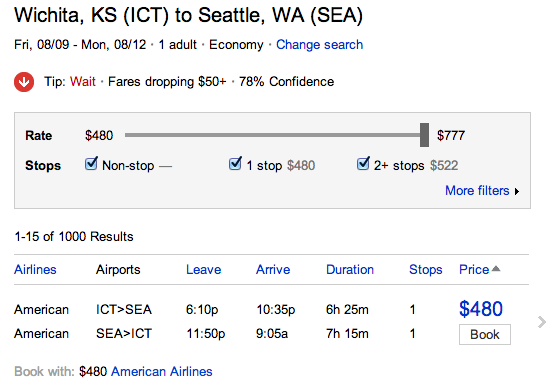

I really don’t have much experience or luck in trying to predict when the price will go down. Bing Travel has a price predictor that attempts to do this for you, though I haven’t actually tried it. One challenge is that Bing looks at the overall market and does not distinguish between preferred carriers or travel times.

If you’re willing to be that flexible, you may not need a prediction tool. I’ve seen prices halve from $400 to $200 if you’re willing to fly in the early morning or switch from United to Allegiant. Let’s just say convenience has its price, too, and there is a good reason why such discrepancies exist.

Conclusion

My own strategy is to start looking far in advance — months out, even — and book when I find a price I’m comfortable with. Maybe fares will go down a little after that, but I usually have a good sense of the best fares for that market or develop one as I look. By starting early, I give myself the largest possible window to find a good fare.

Just like the airline, counting down the days until it loses any chance to sell that seat, you have a limited window before you need to brace yourself and pay whatever it takes to get there. The only thing worse than paying too much long in advance is seeing the cheap fares disappear and get stuck with a costly last-minute booking because you were unwilling to pull the trigger earlier.