Last week, I had a wedding in Memphis, TN, which afforded me my first visits to the State of Tennessee (and Mississippi) along with a trip to Memphis International Airport (MEM). Five years ago, I wrote about Delta’s decision to de-hub Memphis in favor of building up Seattle, which was originally designed to chop volume while retaining a few spoke destinations from Memphis. However, as we later came to discover, Delta would cut most of the services from Memphis to other cities, such as Seattle, Boston, and Fort Lauderdale. American Airlines is actually larger than Delta at Memphis, which is a far cry from what it used to be like.

The “walk in Memphis” airport is unlike any other that I’ve seen in an airport that used to be a major hub, in the sense that the airport feels like time-travel back to the 1980s.

Similar to my Los Angeles Airport series that I published last month, this will be another “three-parter” story where I’ll write separate posts about the past, present, and future of Memphis/Shelby County airport, which played a huge role in the history of American flying. I’ll showcase some of the hidden gems at the airport that exists in the facilities today, and provide an overview of some of the modernization plans of the future.

For this post, I’ll provide a refresher trip down MEM-ory lane for those interested in some of the #AvGeek components, and how the rise and fall of Memphis airport as a hub is one of the most fascinating stories in U.S. history. Part two will review Memphis Airport in 2018, and Part three will showcase the enhancements coming to Memphis airport in 2020 and beyond.

Early Beginnings

Memphis airport was opened in 1929 as Memphis Municipal Airport, and over the course of the following decades, its airport planning commission sought to be forward-thinking in terms of creating facilities that would keep pace with advances in commercial aviation. A new terminal was constructed in the early 1960s by Roy Harrover and stands today as the primary entrance facility for departing passengers on scheduled air service flights.

During World War II, MEM had been controlled by the U.S. Army, and it served as a hub for sending aircraft overseas as well as for cargo and military supplies. This association would eventually be recreated in the early 1970’s when FedEx was created in Memphis. The company built a sorting facility and administration on the airfield, designed to make Memphis the busiest cargo airport in the world.

The Republic Years

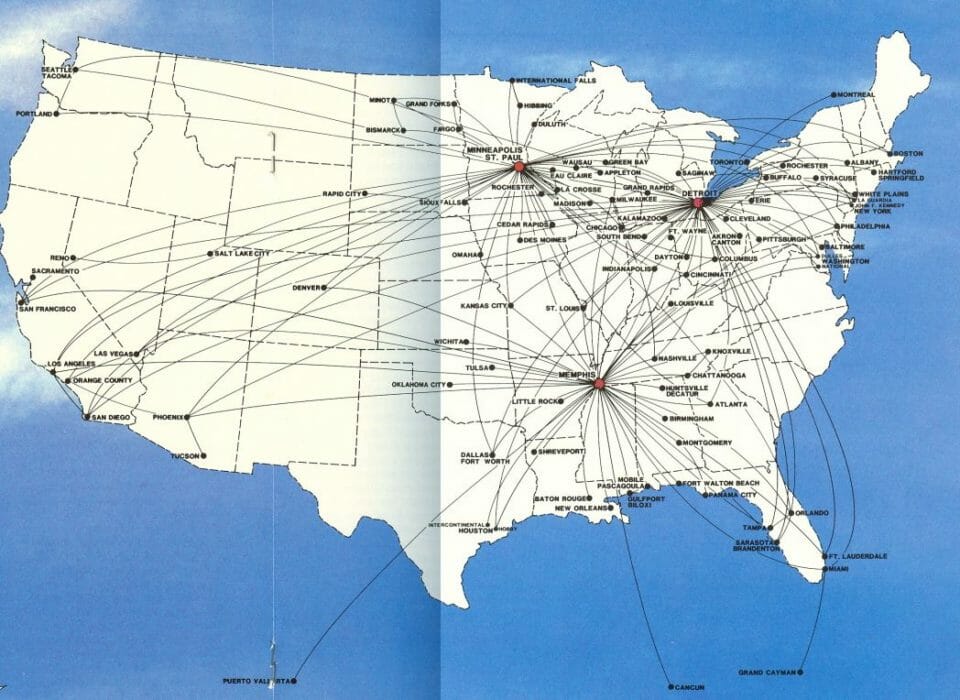

Memphis also became a hub airport for Republic Airlines in 1985. Republic was a Minneapolis, MN-based airline that had formed in 1979 from the merger of North Central Airlines and Southern Airways after deregulation. True to their names, North Central was prominent in the Upper Midwest region with hubs in Minneapolis, Detroit, Chicago, and Indianapolis, while Southern was dominant in the Southeast, principally hubbed in Atlanta but also with a large base at Memphis. Due to the nature of consolidation after the deregulation act of 1978, airlines began to be more strategic about their hub locations, and hence Memphis was chosen as the surviving hub of the Southern-North Central merger when Republic was created, as Atlanta was home to Delta, the 800lb gorilla.

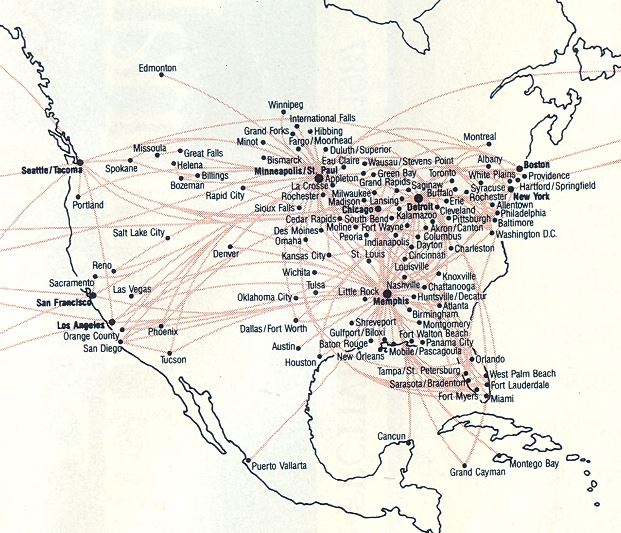

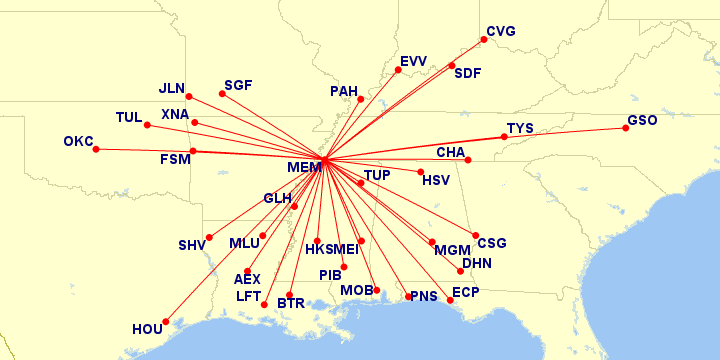

Republic did not last more than 7 years, as it was eventually gobbled up by Northwest Airlines. However, Northwest retained most of its hubs in the U.S., including Memphis, which was connected to many secondary and tertiary markets all over the South and Southeast, namely in Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Tennessee.

Memphis worked well for Republic given that it operated a fleet consisting entirely of Boeing 727-200s, McDonnell Douglas DC-9-10s/30s/50s. Northwest would eventually add 757-200 and MD-80 flights to Memphis as well, and connect Memphis to small markets using aircraft like the AVRO Regional Jet, British Aerospace Jetstream 31 or Saab Fairchild 340, using subsidiary carrier Northwest Airlink.

Northwest Years: 1986-2008

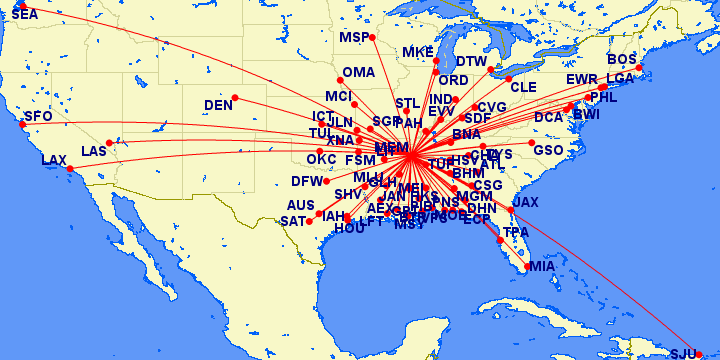

Memphis thrived as a hub for Northwest, with a mix of domestic-and-international service to markets all over the country, as well as Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, and even Amsterdam. When Northwest and KLM formulated their joint venture in 1995, KLM actually began flying to Memphis, at one point utilizing the famous “mixed paint” DC-10 that featured Northwest and KLM colors.

That being said, Northwest did little to grow the Memphis hub over the next twenty or so years, despite the fact that it remained one of its three primary hubs. The Memphis business market wasn’t thriving, and somehow, low-cost carriers like Southwest didn’t seem interested in flying to Memphis to compete locally with Northwest, so everything just remained status quo. Northwest would eventually run into challenges in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s that were far more pressing, such as dealing with strained labor relations, soaring fuel prices, 9/11, and the impact of the SARS outbreak and war in Iraq/Afghanistan that depressed premium travel.

Northwest also invested more heavily in its other “crown jewel” hubs, such as Minneapolis/St. Paul and Detroit McNamara, which not only had stronger origin-and-destination traffic but also were backed heavily by high-yielding business demand. The Twin Cities, where Northwest was headquartered, is home to a lot of major fortune 500 companies such as 3M, Target, General Mills, Best Buy, United Health, and Detroit is obviously home to the major automobile corporations. Minneapolis/St. Paul served as a great East-West connecting hub and gateway to the Great Plains/Upper Midwest, while Detroit was the primary gateway to Europe and a few Asia-Pacific markets.

Northwest also invested in its “Midwest Heartland” strategy which entailed building up focus cities in Indianapolis and Milwaukee, where it could take the lion’s share of local traffic heading to major business markets like New York and Boston. It also had focus cities in Seattle/Tacoma, Portland, and Los Angeles, where it had ties with local partners like Alaska Airlines or foreign carriers that operated transpacific routes into those cities.

So where did that leave Memphis? Not with much. Memphis did not have anywhere near the volume of O&D, business demands, or geographic advantage, that Northwest needed. But, Northwest had plenty of old aircraft, like the DC-9 and its Mesaba/Airlink planes, which needed to be flown somewhere. Memphis was an easy place to put them, until Delta came into the picture.

Death by Delta

When Delta merged with Northwest in 2008, it was presumed the hub’s days were numbered. Even though Delta promised to keep Memphis open as a hub, even retaining pre-merger Northwest’s flight to Amsterdam (by then down-gauged to a 767), people didn’t expect the hub would last.

This was largely due to the fact that Delta’s massive Atlanta hub was located a few hundred miles away. As-is, many local Memphis flyers were accustomed to driving to nearby cities, such as Little Rock or Nashville, where low-cost airlines like Southwest or AirTran had a presence. Atlanta was not only within driving distance but also had lower average ticket costs because there was more competition at ATL airport. Furthermore, there were obviously way more options at ATL airport given its massive size and scale as a Delta hub.

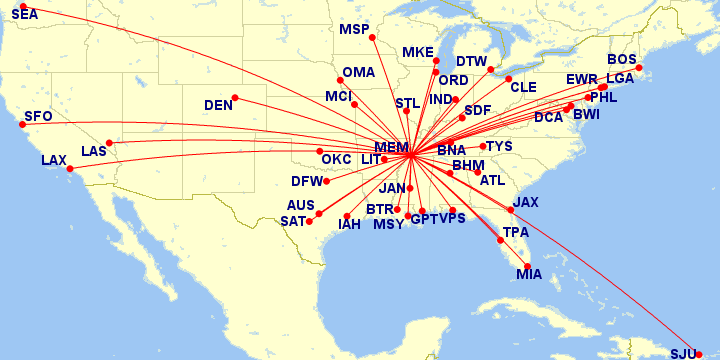

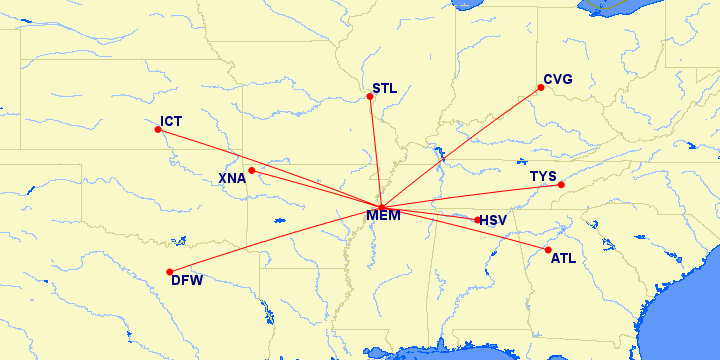

When Delta finally axed the Memphis hub in 2013, the plan was to retain some level of service to several dozen cities, albeit at a much smaller schedule. The carrier retained service to core cities like Los Angeles, New York, Las Vegas, and Chicago O’Hare, along with its hub cities, but Memphis ultimately lost service to all of the small secondary and tertiary markets in the Southeast and Midwest, along with service to some smaller markets like Kansas City and St. Louis.

Terminals

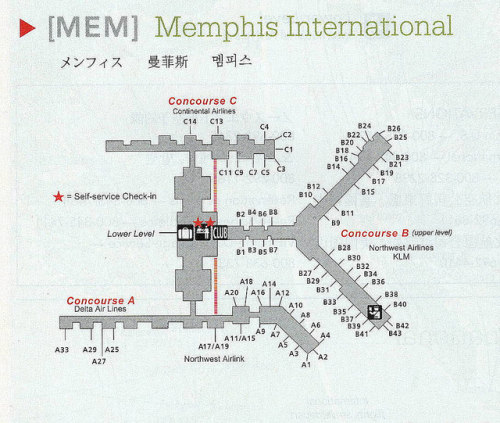

Memphis airport was once utilizing three concourses: A, B, C, with the heart of Northwest/Delta’s operations taking place in concourse B, which is shaped like a “Y.” The advantage of MEM as a connecting airport was that walking distance was fairly minimal between gates, and for originating and terminating passengers, the walk to the main concourse was also fairly short.

Sadly, with the massive schedule reductions at MEM, the airport has been able to consolidate a significant chunk of the space, with the entire concourse B shut down for the time being. The good news is, however, that Concourse B will re-open in a few years as part of a newly modernized facility.

Stay tuned for Part II, where I will provide more insights into how Memphis airport is doing today, and Part III, which provides an overview of the Memphis airport of tomorrow.