Critics of the Gulf carriers may wish to pay special attention to Emirates’ latest decision to suspend plans to launch nonstop service to Panama City, and re-evaluate the validity of allegations against the U.A.E. government for unfairly subsidizing loss-making long-haul routes on homegrown carriers. Though claims against the Big 3 Middle East Carriers – Emirates, Etihad and Qatar Airways – for capacity dumping and trashing fares in global markets are certainly not new developments in the global airline industry, there has never been a case where one of these carriers has abandoned plans to launch a well-publicized route.

Emirates, as well as Qatar and Etihad, have maintained their innocence for years and even gone as far as to divulge that they are not insulated against external pressures that cause downtrends for global airlines, such as rising oil prices, economic woes and competition. Hence, the postponement of Panama City may be the first substantiation of this truth.

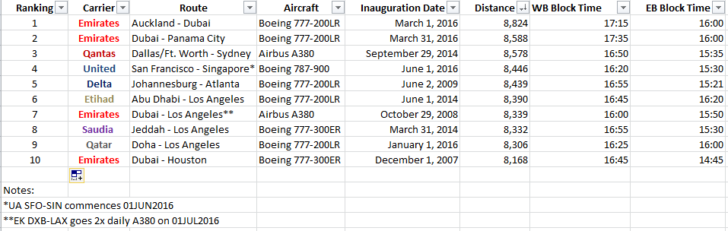

Panama City was initially announced by Emirates in August 2015 with an expected launch date of February 1, 2016. It was soon to become the world’s longest route by flying time (blocked at 17 hours and 35 minutes west-bound) overtaking Qantas’ Dallas/Ft. Worth – Sydney route at 16 hours and 50 minutes westbound. In mid-January, several weeks before the February 1 launch, Emirates announced it was delaying the startup date until March 31, 2016, although attempted to cover face slightly by announcing that it would launch a new nonstop route to Auckland from its Dubai hub on March 1, a day later than the Panama City flight was expected to begin.

RELATED POSTS:

Emirates announces Dubai – Panama City flight: the new world’s longest flight

Starting today, Emirates will launch the world’s 1st and 2nd longest flights

Auckland has instead taken the title of world’s longest route (by distance) while Panama City would still hold the qualification of world’s longest flight by block time. However, for the first time in its history, Emirates has shelved plans to launch service to a new intercontinental market, as it announced on March 2, 2016 that it was postponing Panama City until further notice. By de facto, this entitles Emirates’ Auckland service, which was intended to be the world’s #2 longest route after Dubai – Panama City, as the world’s longest route by both distance and block time.

Copa codeshare initially delayed startup, but also did not improve load factors

Emirates, nor any of its Middle Eastern counterparts, has never delayed nor cancelled a highly-glamorized route, especially to a market such as Panama City which is often phrased as being, “the Dubai of Latin America.” A further look at the similarities between DXB and PTY bears uncanny resemblance. For one, both cities are located centrally between to massive population centers: Dubai between Asia and Europe, Africa and the Middle East, and Panama City between North and South America and Europe. Both are home to relatively modest populations of less than 3-5 million inhabitants, yet boast skylines with towering skyscrapers, apartment blocks and high-rises.

From a transportation services and logistics perspective, the two cities perhaps have more in common than any other pair of global markets in the world. The Panama Canal is obviously the premier shipping port for the Americas, and the air transport market – home to one of the most profitable airlines in the world, Copa – is built entirely on international operations using a single fleet type. The same strategy is used by Emirates: all international destinations, no variance in fleet (all widebodies) and essentially supporting a network built entirely on connections.

Emanating from this, both hubs also are positioned between politically and economically tumultuous geographies, with Dubai located near much of the turmoil in the Middle East and Panama City close to the volatility in Venezuela, Brazil and some of the Central American nations. This, of course, can sometimes be advantageous when each has entrenched presence in markets where there is sufficient demand for air travel, but the threat of entry from competing, yet risk-airlines, remains low.

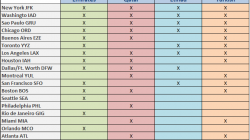

Key to the success of Emirates’ Panama City route would have been an enhanced codeshare agreement with Copa. For Emirates, growth in Latin America has been limited to alpha cities such as Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires. Notably, its Middle Eastern counterparts, as well as Turkish Airlines, serve the same markets, as all of them face similar roadblocks preventing expansion in the continent: lack of long-range aircraft, high-altitude airports preventing nonstop service without takeoff penalties, capacity and infrastructure-constraints and a sluggish economy.

Copa was designed to be the key to overcoming all of those challenges for Emirates. The 737-operated carrier offers numerous daily flights to markets in Central and South America from Panama City’s Tocumen hub. Emirates passengers would have been able to access markets like Bogota, Caracas and Mexico City offline via Copa that wouldn’t have been achievable on Emirates’ own metal for reasons stated above.

The initial start-up date of February 1 was postponed due to delays with implementing its codeshare with Copa and rescheduled to launch on March 31. The codeshare eventually went live in early February and initially only covered a limited number of routes. Copa was able to place its flight numbers on Emirates’ flights between Panama City to Dubai, while Emirates placed its code on Copa’s subsidiary carrier, Copa Colombia, to Barranquilla, Bogota, Medellin and Cali.

According to CAPA, purportedly, the drama and delays surrounding the Copa codeshare could be traced to Lufthansa – one of the most vocal opponents of the Middle East carriers – and also a Star Alliance member that launched Panama City service on March 1, 2016 to Frankfurt. The Lufthansa route, operated on its low-cost subsidiary carrier, “Jump,” is codesharing with Copa, also a Star Member, on a number of Latin American routes. As Star Alliance has strict codesharing rules, and Lufthansa plays a heavy hand in influencing the permissability of Star Alliance members seeking to partner with external carriers, Copa likely encountered resistance to expanding the Emirates codeshare and further developments have fizzled, for now at least.

Even with the aid of Copa, Emirates would have encountered a saturated market in Panama City

Emirates likely didn’t anticipate that the Copa codeshare plans would have encountered as many stumbling blocks as it ultimately did, although it is possible that the restrictions may have been gradually relaxed over time. But it also didn’t help that Turkish Airlines also announced it was starting service to Panama City in May 2016, utilizing an Airbus A330-200 thrice per week in a triangular Istanbul – Bogota – Panama City – Istanbul rotation. Turkish is a fellow Star Alliance member, and therefore does not have to clear the same hurdles as Emirates to partner with Copa. Turkish also tends to be more conservative when launching new long-haul markets by using a sub-daily schedule to monitor demand and then adjusts capacity and supply accordingly. Emirates, conversely, tends to open virtually all of its new long-haul markets using a daily schedule.

Turkish will join Iberia, Lufthansa, Air France and KLM in Panama City as long-haul carriers operating into Tocumen airport. TAP Portugal will end its thrice weekly Lisbon – Bogota – Panama City service on March 27, contending that a limited onward feed from its Lisbon hub was limited to Europe and therefore not as appealing. Lufthansa even delayed its Panama City launch, originally scheduled to go live in October, to March 2016. It is also noteworthy that Lufthansa converted its Panama City route from Lufthansa mainline to Jump, indicating that premium demand for Panama City was lower than initially forecasted.

Emirates, unfortunately, did not have the same flexibility to make adjustments with its Panama City operation upon encountering challenges with oversaturation and low advanced bookings. Therein lies the high-risk associated with operating ultra long-haul routes, even when oil prices are low. For starters, Emirates does not possess a widebody aircraft type with a smaller seating configuration to match supply with demand. Secondly, Dubai – Panama City is 3,000 nm further than Frankfurt – Panama City, meaning that even with a smaller frame aircraft, such as 787-800 which only has a maximum range of 8,500 miles, there wasn’t an alternative aicraft to operate the route other than the 777-200LR series. Finally, Emirates likely couldn’t justify the cost implications of a sub-daily operation when it came to staffing airport resources and attracting high-value fliers.

A lesson in humility for Emirates, or seizing an opportunity when it cannot afford to wait?

Perhaps it is Emirates, rather than its critics, who has learned a lesson in humility, but either way, the carrier appears less than apologetic for canning its Panama City services, which would have been its first foray into Central America. On paper, it is somewhat puzzling that it failed to meet its own expectations to expand further into Latin America, given its youthful history, political resilience, strong capital and generally well-advised strategic decisions. But perhaps the decision came down to taking action based on circumstances that were within and beyond its locus of control. The protectionism it encountered in Panama City – be it truthful or rumored – was likely outweighed by the opportunity to expand into Auckland before its competitor, Qatar Airways, seized the moment. Its brand awareness in New Zealand is obviously far more important than Panama City, as one market is isolated and desperately in need of fewer multi-stop connections to reach global markets, whereas the other is fairly well-served.

Whether or not Emirates will ultimately serve Panama City remains to be determined. In the meantime, Emirates has another backdoor gateway into the Latin American markets – through its codeshare partnership with jetBlue and, to a lesser extent Alaska – over markets that Emirates serves in the U.S. From Orlando, for example, jetBlue operates service to Mexico City and Bogota, both of which can be leveraged to facilitate onwards connectivity to Emirates’ Orlando flight.

Furthermore, the threat of competitor Turkish Airlines may be underplayed here as a formidable contender with Emirates’ growth plans. In many ways, Turkish and Emirates share similar strategies, with largely pro-aviation governments, ideal geographies between massive geographical crossroads, and low-cost structures. Furthermore, Turkish has many advantages that Emirates does not have: narrowbody and widebody fleet flexibility, a massive origin and destination base at its Istanbul hub, as well as the nation of Turkey as a whole, and a less hostile perception in the global marketplace.

Of course, Turkish also has its own challenges, namely in the form of infrastructure constraints at its Ataturk hub, safety in the Middle East (as well as in its own backyard) and bilateral restrictions that limit its expansion. But Emirates and others are starting to notice that its a force that must be reconciled with, and its cost structure, fleet flexibility, alliance membership and global perception are not to be understated.

The world is evolving, and for once, Emirates is being humbled.