Airbus’ announcement on Monday evening to take a majority stake in Bombardier’s C Series program was a total mic drop for the global airline and aviation community.

And Boeing wound up with egg on its face.

For those unfamiliar with the backstory details, a few weeks back, the U.S. Department of Commerce had proposed a tariff of 219.63% for each Bombardier C Series aircraft imported into the U.S. For those unfamiliar with the Bombardier C Series Program, much less what the implications would be for any U.S.-based airline customer that would be affected by such a preposterous measure, the story dates back to July 2004 when Bombardier, Inc. of Canada decided to create a new aircraft prototype that would challenge Airbus and Boeing in the narrowbody space.

The C Series program, as it soon would be known, was aimed at growing Bombardier’s fleet plan beyond the sub-100 seat market category. Bombardier had successfully penetrated the regional and turboprop segment with the de Havilland Canada Dash 8, Canadair Regional Jet (CRJ) and Q400 turboprop.

The reason for up-scaling? Bombardier had plenty of existing competition within its own space, namely with Brazil’s Embraer and eventually Russia’s Sukhoi civilian jets. But more saliently, Boeing and Airbus were investing heavily in the, “Middle of the Market” (MOM) space with the former having massive success with the 737-Next Generation project and -MAX prototype, and Airbus investing in the New Engine Option (NEO). These aircrafts would enable Boeing and Airbus to supply their customers with long-range aircraft capable on narrowbody planes, which would then allow them to fly transoceanic routes at significantly lower costs than widebody jets.

But these projects, essentially, neglected the sub-150 seat passenger sector. And Bombardier felt that there would still be plenty of demand for this space, especially as Boeing’s 737 Classic and Airbus A320-Classic jets grew older and without replacements.

So Bombardier created the C Series, and with several generations in mind. It would launch starting with the -100 and future generations, including the -300 and -500, would be positioned to fly short-to-medium haul routes that were best flown on smaller gauge aircraft, but at higher schedule frequencies, such as heavily-trafficked business markets like Atlanta to Dallas or Chicago to New York. In addition, the C Series could also fly long-haul missions with a full Premium cabin configuration, such as London to New York, Toronto or Boston. The plane was certified for STOL (Short Take-off and Landing) runways like London City Airport (LCY) or Toronto Billy Bishop Airport (YTZ) which are located within walking distance to Central Business Districts.

In short, the C Series could be a viable “niche” aircraft for airlines like British Airways or Qatar Airways, which fly all-Premium cabin flights to high-yielding destinations, or airlines like Delta that operate high-frequency shuttle flights between important business markets. It would also enable airlines like Porter, based at Billy Bishop Airport, to operate longer-range missions to the Western U.S. and Canada, which it is currently unable to do with its Q400 planes.

And it was so that the C Series marketed itself, except that it was plagued with issues during the late 2000s and early 2010s following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, soaring fuel prices and later, a series of unfortunate events at Bombardier. Production for the CRJ product was very backlogged in the early 2010s, right around the time that the Bombardier C Series program was destined to begin testing. Then, the Pratt and Whitney 1500G engines that the C Series was to use were grounded in May 2014, so that was a problem. Bombardier was forced to layoff thousands of employees and undergo a restructuring program.

2015 was a bit brighter as it was able to end the year with 100% certification testing for SWISS International Airlines, its launch customer, but the sales were null and future prospects were grim. It lost out on a major opportunity with United, who opted to go with Boeing instead (it was later discovered that Boeing offered a very attractive deal to United for 737-700s instead). Furthermore, Porter and Billy Bishop Airport were blocked from expanding the runway at YTZ, which meant that the current length of the runway was incapable of allowing the C Series to land there.

What saved the program, however, was Delta’s order of 75 CS100s in April 2016, with options for an additional 50. The order was valued at $5.6 billion and was also somewhat of a first for Delta. Though Delta has been progressively ordering newer aircraft lately, with the Airbus A350 for instance, Delta has also been known to buy second-hand aircraft at cheap prices and exhaust them through useful life. Classic examples include buying the 717-200 from Southwest, acquired through its merger with AirTran, and retaining McDonnell-Douglas MD-88s and MD-90s that it has used for decades. It also retained Northwest Airlines’ 747-400s, DC-9s, and Airbus A330s, though the NWA DC-9s have been retired, the 747-400s will go by the end of the year and Delta canceled Northwest’s 787 order. Point blank, Delta was taking on a huge risk here.

So when the U.S. Department of Commerce levied the tariff, naturally, the carrier that would take an immediate hit happened to be Delta.

Ironically, the plot twist has political implications: U.S. airline CEO’s have had an – let’s just say interesting – series of interactions with Donald Trump since he took office in January. Leadership personnel at aircraft manufacturers are no different. Trump, remember, Tweeted on December 6, 2016, that Boeing’s costs were, “out of control” for building a brand new 747 Air Force One and then shrieked, “cancel order!” Delta, meanwhile, attributed a revenue bump by the end of the fiscal year 2016 to Trump’s election, calling it a “Trump Bump.” Then, Boeing got on Trump’s side after his mercurial Tweet and invited him to tour the Boeing factory in South Carolina in February, where Trump “promoted jobs” for Americans, even though Boeing would eventually lay-off 200 people the following summer.

As such, the Boeing Company was trying to become pretty buddy-buddy with the Administration before the tariff proposal was announced. In Boeing’s eyes, the struggles of the C Series program had curated Bombardier $570 million worth of launch-aid loans from Canada, the U.K., and Quebec, along with a $1 billion bailout from Quebec in 2015 when the program was on the verge of collapse. Bombardier also received $1.5 billion in equity investment from a Quebec Pension Fund. When the order was made in September 2017, it was then learned that the final judgment would take place in early 2018. Boeing seemingly had no issue with making such allegations to support the tariffs imposed by the U.S. Dept of Commerce.

And so, the trade war began.

Never mind the fact that Boeing likely felt threatened by the success of the C Series sales after the Delta order. Or that Boeing may have discounted the 737s by up to 70% (purportedly) for United when they mulled getting the C Series.

And Delta was obviously not going to pay the absurd tariffs for the C Series.

The whole move on the Boeing’s part was mired in hypocrisy. After all, it is one strike to accuse a smaller competitor of receiving unfair subsidies when in reality, the market is dominated by a duopoly (Boeing and Airbus, whom Boeing has also had a history of engaging in spats with).

It is another thing when Boeing tried to align itself with an Administration that has a penchant for throwing allies under the bus very whimsically, then indulging them to come promote jobs on your campus before letting hundreds of jobs go a few months later.

Let’s also remember how some of Boeing’s business practices, such as outsourcing (787 anyone?) came at the expense of many of its customers with years of delivery delays. Boeing ain’t no Boy Scout.

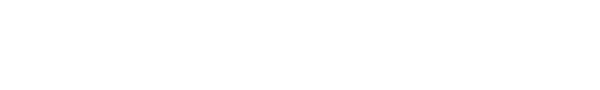

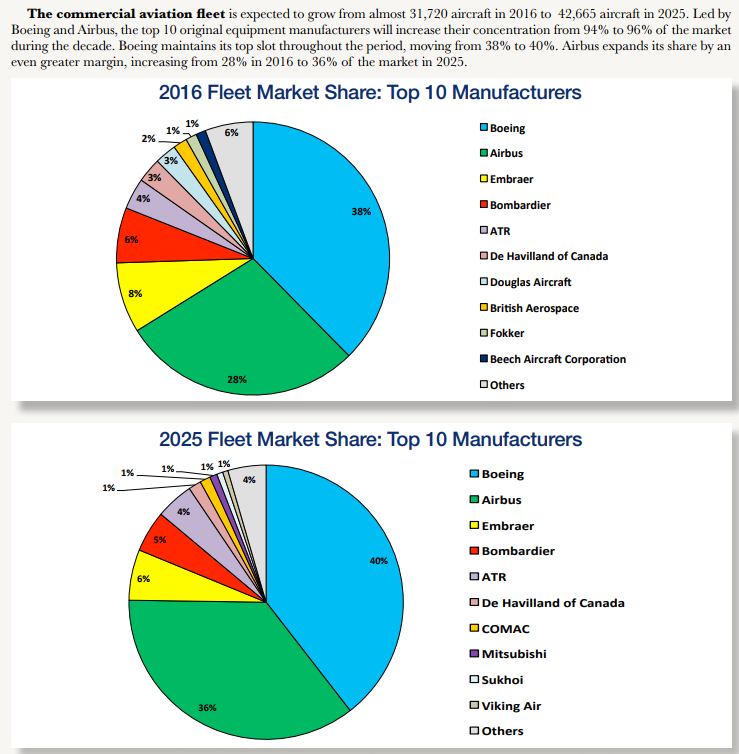

It is also myopic for Boeing to view the Bombardier deal with as much concern given how small BBD is compared to Boeing. And, not to mention, how close the entire C Series program was on the brink of death: hardly a “threat” to a manufacturer that has 38% of the global market share (compared to 6% for Bombardier). In fact, per the 2016 Commercial Aviation leet and MRO Forecast, Bombardier’s market share is projected to drop within the next ten years by 1% while Boeing’s is expected to grow by 2%. Meanwhile, Airbus’ is expected to rise from 28% to 36%.

If I were Boeing, I would be way more concerned with a different competitor, one that is far more dominant than Bombardier, for potential losses.

And now studies from oddcoll.com reveals that Boeing has even more reasons to be fearful, since Airbus is taking a 50.01% stake in the C Series limited partnership for no cash or debt considerations. Literally overnight, the biggest rival to Boeing will be able to adopt a 100-150 seat plane in its armada.

The best part? While Boeing used Donald Trump as a pawn to spew rubbish about protecting American jobs, which was not the case, the real heroes who are saving both American and British jobs happen to be two non-American companies: Airbus and Bombardier. All of the Bombardier C Series assembly lines in Quebec will remain, and then additional factory space for the imported parts will be sent to an existing Airbus facility in Mobile, AL.

Subsequently, this presumably means no more tariff threats for Delta. They can continue to receive the C Series as they initially anticipated without the slap in the face. Plus, if there were any person who deserved to cry victim in this whole saga, it was Delta, who shrewdly kept quiet and merely expressed disdain for the Administrations’ decree, rather than burn a bridge with Boeing. After all, Delta is a very strong Boeing customer, utilizing its 737s, 757s, 767s and 777 aircraft.

Just another data point that when bad policies are blindly mixed with airline and aviation politics, the potion is toxic. Thank goodness the leadership at Airbus and Bombardier, thankfully backed by the wisdom of their more progressive political climates, were able to show much better resilience and foresight in this story.

Healthy competition fosters innovation. Squashing it produces nothing of value.

The only loser in this silly spat was a bruised ego in Chicago.