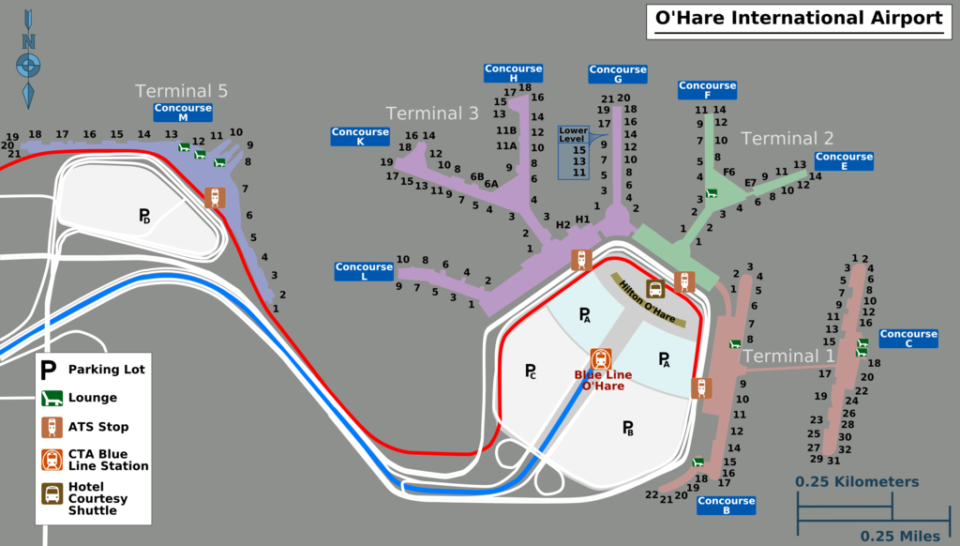

Earlier this week, it became known that the City of Chicago was close to signing an $8.5 billion deal with American Airlines and United Airlines to expand the number of gates at O’Hare International Airport and revamp terminal facilities. The key tenants of the negotiation, which came about as a 35-year lease agreement ends in May of this year, entailed increasing the number of gates from less 189 to 220, revamping Terminals 1, 2, 3, and 5, and co-locating international flights on American, Delta, and United with their fellow alliance partners in a manner that was much more passenger-friendly.

But there is a new fly in the ointment as American is coming out in opposition to the deal, alleging that the city awarded United with additional dates under a “secret provision” at the last minute.

Under the current plan, American has 35.3% of airline capacity at O’Hare, while United has 45.5%, give or take a few percentage points, broken down by seat share. As-is, there is a 14-gate difference between the two carriers at ORD, with American having 66 gates while United has 80. This difference, however, will drop to 9 upon completion of the 5-gate facility this spring, which has been dubbed, the “L Stinger” gates behind Concourse L at Terminal 3, used by American.

The ordinance permitting the Chicago Department of Aviation and American Airlines to build these gates was signed in March 2016 and will be the first major expansion of gate capacity at O’Hare since international Terminal 5 was built in 1993, according to the City of Chicago. In fact, this will actually be the first domestic gate expansion at ORD since the completion of Terminal 1, where United operates, in 1987.

The gates will allow up to 45 new daily flights for American, who currently operates 498 daily flights to 122 destinations from ORD. However, they will also only be able to accommodate regional jet flights due to space constraints. Furthermore, all of the current regional jet flights that are handled by Concourses H/K, which formulate the two central, “Y-Shape” buildings in the middle of Terminal 3, are purportedly going to move to the L-stinger gates, thereby leaving H, K, and American’s L Concourses primarily for mainline aircraft use. Concourse G, and now the L-stinger gates, will be the designated regional flight departure areas.

And, American is indeed beefing up its O’Hare operations and making some stylistic changes to the ground experience at ORD. Over the next coming months, it is adding new service from Chicago to Bangor, Maine, Vancouver, Venice, El Paso, Wilkes-Barre, Burington, Calgary, Charleston, Missoula, Myrtle Beach, Portland, Maine, Savannah, and Wilmington, N.C. It is also converting its 15-weekday roundtrip Chicago-New York LaGuardia flights to its American Shuttle brand in early April, which will offer hourly departures with designated check-in and boarding areas in Terminal 3. The Shuttle brand is offered by American from New York LGA to Boston and Washington Reagan, and Delta similarly offers a shuttle product on the same routes as well.

So while American is indeed very committed to its Chicago O’Hare hub, it was also hoping that in signing the new deal with the City of Chicago, the distribution of gates between it and United would remain as close to parity as possible – or at the very least, no greater than the current difference of 9 gates (once the L-stinger concourse opens). As we’ve come to discover, United, purportedly, reached a deal with the city over 18 months ago to receive 5 new gates of their own, allowing them to add an extra 35 daily flights, according to Skift. American contends that this deal wasn’t reached 18 months ago, and rather, was cut last-minute by Mayor Rahm Emanuel secrecy with United.

Both United, Emanuel, and Aviation Commissioner Ginger Evans have denied this accusation. While nobody really knows what will happen if American chooses not to sign the deal as a result of their accusation, Emanuel and others appear to be pretty optimistic about the deal going through anyways. Since the project is going to financed by increased fees that airlines will be passing on to passengers, it obviously needs a carrier with American’s size and scale at O’Hare to re-sign lease agreements for the 71 gates it will have come May.

American has asked for O’Hare to grant them three additional gates as a compromise measure, but to date, this has been denied by the city.

This is definitely a tricky situation, and like almost every political decision that involves the City of Chicago, there are enough plot twists to make one’s head spin.

Thankfully, the rockstars at USA Today, Bart Jansen and Ben Mutzabaugh, have done a great job in distilling some of the ambiguity, and we can maybe deduce what sequence of events took place that ultimately led to why and how the communications broke down.

And, here is how I understand it, to the best of my abilities. I could be wrong on some, most, or all of these assumptions, but I’ll go ahead and take a stab, anyways. For the record, I have no insider information based on interactions with anyone at American, United, Chicago O’Hare, the City of Chicago, or otherwise, beyond what is available to the public.

- At the macro level, the whole reason why these negotiations are happening in the first place is that American and United signed a lease agreement with O’Hare in 1983 that gave them both veto power on projects, such as upgrading and maintaining terminal facilities

- That lease duration was for 35 years and is expiring in May. The renegotiations will presumably NOT grant the airline such veto powers, because the politicians are now fully aware that American and United will not fund projects that, in their minds, are “helping competitors,” at ORD even though both United and American collectively maintain over 75% of the capacity at ORD.

- Everything boils down to two magic numbers that come in 3’s or 5’s:

- American, for its part, has surrendered five gates at ORD over the past few years (due to a myriad of events such as the settlement agreement with the US DOJ to merge with US Airways, an exchange with United for gates at LAX, and a sublease to Delta).

- In 2016, American then asked to build five gates of its own, right around the same time that United wanted five new gates of its own as well to keep things balanced.

- Presumably, back then, the negotiations for the $8.5 million deal were already in motion, and the plan to move Delta to Terminal 5 had already been in the works. United asked for O’Hare to give up the 8 gates Delta would vacate to United, but the city compromised and offered only 5 to United, rather than all 8, and 3 to American, but American rejected this offer.

- United then decided to quietly take the city’s offer, and this is where the confusion began. American wasn’t fully aware of this and did its own thing in the interim.

- Now, American is coming back and accusing United/O’Hare of not being transparent. It is quite plausible that they were truly unaware that United and O’Hare had come to this agreement, OR, in a devil’s advocate situation, they knew all along and intentionally planned to wait as close as they could to the negotiation deadline in an attempt to up the stakes, claim additional value and hope to gain more concessions.

- There are data points which may hint that American had ulterior motives: it first stated that there was collusion between United and O’Hare, then later said it was a miscommunication, and now are saying that they are still interested in the 3 gates that were initially offered because it’s better than nothing.

- The City of Chicago is likely sick of all of the back-and-forth banter and politics and just wants to get the deal sign, sealed and delivered. After all, with the thorns on both sides of their legs (hopefully) being removed come May, they want to press forward and give Chicago O’Hare the facelift that it badly needs.

If indeed these are relevant and credible facts that pertain to the case, then its hard to take American’s side in this battle. The airline has learned some hard lessons in the past from setting its expectations way too high when it comes to political disputes – at a price. The US Airways settlement was one example, which resulted in forfeited slots and asset divestitures in key hubs. Dragging out negotiations becomes extremely costly and nobody wins – least of all the person who stands the most to lose – when the reference points fall victim to framing biases.

As a matter of fact, the Q4 earnings calls for 2017 was ridden with comments of displeasure from Wall Street analysts at the volume of capacity growth that airlines like American and United intend to add this year, especially at their mid-continent hubs like Chicago. Even though these negotiations are intended to reflect a business atmosphere that is several years away, why feel the need to chest-beat now over 5 piddly gates?

Reaching a deal is better than not reaching a deal in terms of maximizing the utility for everyone.

And everyone needs to see it that way, otherwise, nobody stands to win.