I have a friend who works for a major US-based airline. On Monday, he shared an article published in USA Today this week, titled, “Don’t fall for airlines’ ‘unbundling’ ploy,” written by author Christopher Elliott.

In the article, Elliott, a self-proclaimed “consumer advocate and editor at large for National Geographic Traveler” slams US carriers over the ambiguity surrounding their practice of “unbundling” ancillary fees/fares, which are the extra costs a traveler elects (sometimes voluntarily, sometimes not) to pay when they fly, on top of the base fare of the ticket.

As someone who has worked extensively on internal projects pertaining to ancillary sales implementations and is pretty well-versed with the ins-and-outs of the revenue management implications on either side of the coin, for consumers and suppliers, my friend wasn’t very happy with the points Elliott raises in his piece.

Despite the fact that the so-called, “fee revolution,” as Elliott describes it, has been at large for over five years now, he contends the practice is still “misleading” and “problematic” as it continues to guilefully “confuse” customers. Moreover, Elliott asserts that there is no convincing evidence that airlines have lowered their base ticket prices since adopting the unbundling model, a necessary course of action that should have occurred after pricing additional products a-la-carte style separately from the basic fare. Instead, Elliott claims airlines are just adding new fees to their rates and taking more of the consumers’ money.

In summary, he believes it is all a ploy that customers have fallen for, and that it has to stop.

I think that’s a bit extreme. Although I personally do not have any dog in this fight, I’ll be the first to say that Elliott’s comments are pretty exaggerated, if not outright refutable. You can read more about his thoughts on his website, Elliott.org.

Some of it boils down to expectations versus reality. While I do agree that the consumer is entitled to full disclosure of business practice and ought to remain savvy when it comes to bargain shopping, that does not mean they are entitled to, well, a sense of entitlement. Unfortunately, it appears that this exact sense of entitlement is what is clouding Elliott’s view of reality.

There are a few salient points that he mentions in his article, but few resemble the actual dynamics of how the airline industry operates from an economic standpoint. There are some important distinctions specific to air transport that his article completely overlooks.

Just like any regular consumer, I obviously do not embrace the concept of paying ancillary fees, yet I think the logic behind them is perfectly justifiable from the supplier’s perspective. I also don’t think that the lack of transparency is as flagrant as Elliott suggests.

Here’s why.

First, commercial air transport incurs costs in unfathomable ways, and it’s ignorant to believe the airline should be responsible for shouldering all of them

Last time I checked, airlines were for-profit businesses, not charitable organizations nor works of public services.

Airlines are in the business of transportation. Not food and beverage, portering, pampering nor entertaining. Their jobs are centered around carrying passengers between point A and point B safely, and (hopefully) on-time in a clean, secure vessel.

Just as cinemas, Broadway theatres and professional sporting venues are in the business of entertainment, not snacks. If you want popcorn, cocktails or hot dogs, you can buy those items a-la-carte. Nobody seems to take issues with paying $6 for lukewarm Old Style beer to watch the Chicago Cubs lose at Wrigley Field.

Unfortunately, when it comes to air transport, the majority of the masses want to believe otherwise.

Put simply, Americans have become jaded as travel shoppers. As the price of air travel has dropped over the years (which I’ll address shortly), they’ve cozied up to the notion that they know exactly what the airline SHOULD be charging for the price of a ticket.

Furthermore, since airfare shopping represents only part of the travel and tourism purchasing ecosystem, often preceding (or conducted alongside) hotel and rental car research, the consumer habitually loves to cross-compare how the pricing models break down between all players involved, believing that there should be a standardized norm set by the supplier and followed by the buyer.

This shows they know absolutely zilch about how cost breakdown varies dramatically among the major operators in the services industry.

For example, Elliott highlights that an airline doesn’t have to provide a “free” meal or checked bag any more than a hotel company shouldn’t have to provide access to exercise facilities or a rental car, the cost of a license plate. This likely serves to suggest that the hotel industry has a firm grasp over controlling the cost of goods served and knows better than to withdraw certain free “perks” from guests in a vain attempt to drive up revenue streams.

Unfortunately, such an over-simplified analogy does nothing to explain the cost disparity between operating a single flight versus charging for a hotel room. It’s an apples to oranges comparison. A lot of it boils down to the simple, yet key, differences between fixed and variable expenses.

To provide some framework, airlines start to incur costs for operating a single flight months prior to the actual departure date. At first, much of this is back-end, of course, such as paying the salaries of the marketing analysts who plan the schedules, set the pricing tiers, create the inventory, promote the service, etc. and the reservations, ticketing and sales agents who distribute and sell the flight and complete the transaction for the customers on the phone, in ticket offices, or in 3rd-party locations.

All in all, so far, fairly on-par with hotels and the other guys in the services industry.

However, come day of departure, the costs for the airline multiply ten-fold. Labor expenses alone are staggering: the airline has to pay the check-in agent employed at the ticketing counter, the TSA personnel at security screening, the gate agent managing boarding, the guys operating the fuel trucks and gassing up the plane, the guys performing maintenance checks, the aircraft cleaning crews, the catering crews, and the ramp workers loading luggage and tugging the plane at pushback, just to name a few.

Then, wheels come up, and the airline has to pay the cabin crew to operate the plane and serve the customers on-board, as well as Air Traffic Control on the ground to navigate the plane safely to its final destination.

Wheels come down, and the cycle starts all over again.

That’s assuming the plane departs and arrives on-time without irregular operations. Like hotels, airlines are labor and capital-intensive business entities. However, hotels aren’t nearly as detrimentally affected by temperamental weather, tarmac delays, adverse wind conditions, FAA-mandated ground-stops, faulty equipment, IT glitches and security threats.

Every single delay, cancellation or distraction adds additional costs multiplied by X number of passengers and cabin crew members affected.

Hotel laborers also do not require specialized licenses or a minimal amount of flying hours, nor belong to highly unionized workgroups subject to strike at whim.

There’s a saying out there about how to become a millionaire: be a billionaire, and start an airline. One would ever wonder why…

Returning to Elliott’s analogy, a single buy-on-board meal item for $10 went through the process of preparation from a caterer, loading (or unloading) onto the aircraft, consumption (or expiration followed by discard). There are also the soft costs involved of creating the menu, designing the marketing materials and printing them to place in every seat pocket on-board.

Whereas, for a hotel, the “fitness center” is a fixed cost built largely with chump change. Guest expectations are low, and usage is minimal (honestly, how many times have you actually encountered a packed fitness room at a hotel?).

Dumbbells aren’t perishable food items nor do they consume fuel whenever they are carried around by residents.

Every small thing adds up when your variable costs are out of control. Hence, why it makes sense to unbundle them, sell them at a profit to the customers who WANT these frills, and prevent waste.

Maybe airlines should start allowing passengers who use unopened soda cans for dumbbell exercises, starting at $5 per pound.

Second, it is unfair to claim that unbundling is amoral when, in actuality, airline ticket prices have fallen over the decades and has gone largely unnoticed.

As mentioned previously, air transport incurs costs beyond the scope of human understanding with every single flight. One would ever wonder why flying used to be considered a rare luxury, afforded only by the privileged and high-class members of society.

Earlier this year, The Atlantic published an article, written by author Derek Thompson, titled, “How Airline Ticket Prices Fell 50% in 30 Years (and Why Nobody Noticed).” In the article, Thompson draws attention to the fact that one of the brighter spots in the US economy has been the democratization of air travel in the post deregulation era.

Unfortunately, few Americans choose to appreciate, much less acknowledge, this obvious fact. Why are we so jaded? It could be a by-product of generational gaps: many of us still have vivid memories of the pre-9/11 days when flying was much simpler and comfortable, and still had associations of glamor. We expect first class service for penny-pinching prices.

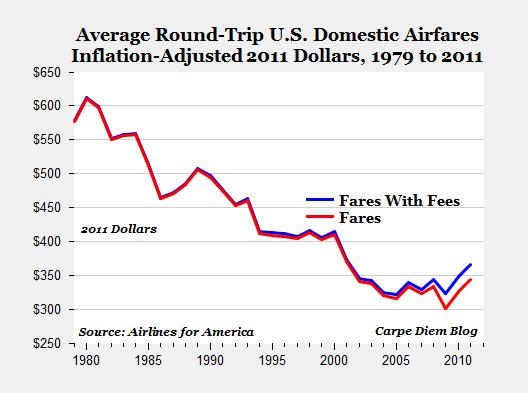

The graphic below, adjusted for inflation, shows how the average cost per flying on a round-trip ticket has fallen 50% since 1978 (Source: The Atlantic):

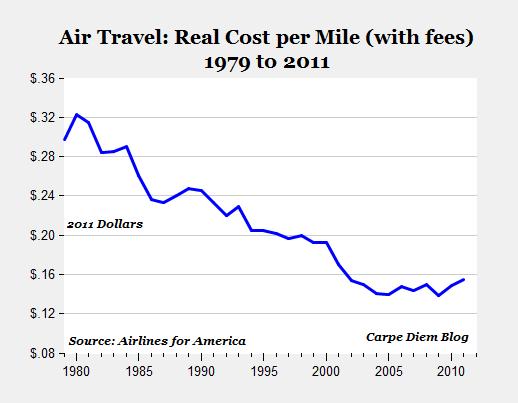

Even more shocking, even with the recent uptick in fees, the per-mile cost of flying has also decreased by half, as shown by the following graphic.

Meanwhile, the number of air travelers has tripled between the 1970’s and 2011.

While it’s true that there hasn’t been an equally offsetting balance as airlines have unbundled, the fact remains that flying has become a cheap commodity that is now accessible to virtually everyone.

Air transportation is not a necessity for survival, which is why complaining over add-on fees looks silly when the consumer was able to score a round-trip ticket for a dirt cheap price.

Third, playing devil’s advocate, look at it from the airlines’ perspective: why WOULDN’T you want to charge for add-on fees? It’s rational!

Prior to 2008, ancillary fees were largely avoidable. Airlines had gradually phased out certain “freebies” offered on-board planes, primarily in the form of complimentary catering and pillows and blankets. This was more of a “cost-savings” measure, as one can imagine, the amount of capital investment required isn’t worth the benefits derived, from cleaning to extra fuel burn to pure wastage.

But then, fuel prices began to spike, and around the same time, airlines started to fall off the face of the earth. Familiar household names such as ATA Airlines and Aloha Airlines, and some barely-new ones such as Skybus, disappeared within weeks of each other. Pretty much every major legacy and low-cost carrier alike – AirTran, Republic, United, Frontier, US Airways, Northwest, Delta, America West, Southwest, Continental, Sun Country – all either filed for bankruptcy or merged between 2002 and 2010.

It’s mind-blowing to think back to how different the industry was hardly a decade ago.

When it became a fight for survival, airlines needed to explore new revenue opportunities, and the minimum level of incremental revenue required was not going to be satisfied from buy-on-board and exit-row seating sales. Rather, airlines had to adopt more unavoidable tactics, namely in the form of charging for 1st and 2nd checked luggage pieces, as well as change and cancellation fees.

The consumer backlash was obviously unfavorable, yet they had no choice. Airlines raked in billions of revenue from the get-go, realizing that they had discovered a new cash cow. Moreover, the opportunities to explore more revenue-enhancing opportunities, and exploit the space even further, all of the sudden seemed boundless.

Most of the network carriers have stayed relatively on-par with each other. First came the introduction of charges for 2nd checked-bags on international long-haul flights to Europe and India, and then came gradual increases in change/cancellation fees on domestic and international tickets in increments of $50. Even Award travel tickets redeemed on frequent flier miles would eventually be subjected to ticketing and change fees.

Some other airlines tried to out-step the evil fee practice to lure away disgruntled passengers. Southwest and (to a lesser degree) JetBlue Airways capitalized on a “no hidden fees” platform by campaigning 1-2 free checked bags and the like. Southwest secretly tried to take advantage of more subtle methodologies to increase revenue streams, like raising charges for unaccompanied minors and pets, as well as incentivizing passengers with Early Bird check-in and boarding options for a nominal fee.

However, it’s debatable as to whether this strategy was sensible for SWA. Notice how Southwest, after acquiring subsidiary carrier AirTran Airways, has maintained AirTran’s checked bag and change/cancel fee policy. It’s no secret out there that even the beloved Southwest, renowned for its “transparency” on fees, is covertly raking in millions each quarter through a secondary source that fell into its back pocket. Moreover, it has remained extremely tight-lipped about which carriers’ fee policy will prevail once AirTran is fully folded into its operations.

Other airlines, however, have gone in the complete opposite direction. Everyone knows by now that Spirit is perhaps the most ruthless of all major US airlines when it comes to ancillary fee practices (and Frontier is trending in that direction as well). The fact that Spirit charges $10 alone for printing off a boarding pass at the airport would have been unthinkable even 5 years ago.

But, regardless of whichever flavor the individual airline chooses to adopt, the whole concept is so brilliant and rational. Looking at Spirit, the largest offender, for example, once you see how much Spirit is charging otherwise for the base fare, it makes complete sense.

It’s no longer about the good publicity and coddling passengers

It’s a model based on providing consumers safe, affordable travel, and that is all that is included in the price. The rest is all in the hands of the consumer. Spirit CEO Ben Baldanza once said (in response to a customer that demanded compensation, but was not entitled to any under Spirit’s contract of carriage) , “let him tell the world how bad we are…[he] will be back when we save him a penny.”

That was back in 2007, around when Spirit converted its business model from “low-cost” to “ultra-low cost” by unbundling everything. That year, Spirit’s pre-tax profit margin’s were 0%, according to CAPA. Allegiant (the other major bottom-feeder ultra low-cost carrier) recorded a pre-tax profit margin of 14% that year, while Southwest enjoyed 11%.

It is now 2013. For Q1 of this year, Spirit’s profit margins stood at whopping 14%, Allegiant’s at 15%, and Southwest’s is 4%.

What does that tell us? The methodology of aggressive product unbundling and targeting niche customer spaces leads carriers like Allegiant and Spirit to produce some of the best financial results among US carriers.

Sounds like a case of tough LUV.

Not only that, as Spirit’s Q1 2013 top-line revenue grew 23% year-over-year, and operating income jumped 33%, passenger traffic also grew 21%.

This places a lot of scrunity around Elliott’s claims about fairness and dishonesty. If Spirit’s practices were truly all that unscrupulous, then they would be losing passengers left and right. The growth in passenger volumes for Spirit only speaks to its ability to gain traction in a space that Southwest and other airlines largely occupied in previous decades.

It’s not the airlines’ fault if the consumer opts to purchase the ticket, enticed solely by an attractive price, without reading the penalties, fare rules and associated charges. It is all printed on their websites and on the fare rules and regulations.

In his article, Thompson alludes to how bargain-hunters “experience a dopamine rush (literally) when they find great prices.” Following this, of course, the “drip-drip” of additional fees “mutes the joy of finding a great price.”

I’ve watched several friends purchase round-trip tickets on Spirit and flown them for the first time, and return home cursing the carrier after falling victim to the ancillary fees, ruing the day they decided to purchase a seat on Spirit and vowing to never fly with them again.

I’ve also watched nearly all of these same friends make repeat purchases on Spirit, and when I question their decision, after all the song-and-dance from the prior wake-up call, the responses are unanimous, “well, I mean, they charged literally over a hundred less than [competing airline].”

This time around, they’ve learned their lessons. They print their tickets at the office and pack a light carry on that fits under the seat in front of them. They bring an empty water bottle that they fill after security screening, prior to boarding and carry a snack with them, or eat at the airport.

It’s a science. Lowered expectations, yes, but you get lower fares in return.

Conclusion: yes, it sucks to pay for things that were once free, but it’s time to get over it.

Obviously, it is a drag to have to pay for things that were once free. Elliott claims that separating anything that was historically part of a product is problematic because it confuses customers. While the “confusion” part is true, its lasting effect wears off after a period of time.

Unless you have been living under a rock since 2008, or haven’t traveled on an airplane, most Americans are fully aware that they’re likely going to have to pay extra for checking a bag when they fly, or a penalty when they cancel.

Five years has transpired since the advent of these fees, and that hasn’t stopped the flying public from taking to the skies. Should carriers continue to seek for new ways to exploit incremental revenue opportunities, yes, there will be some negative reaction, but personally, in my view, I think that the carriers that have NOT adopted the unbundling practice, namely Southwest and to a lesser degree, JetBlue, have more at stake here should they eventually feel pressured to drop their anti-fee stance. At this later stage in the game, suddenly choosing to embracing this model, and going against years worth of marketing campaigns and slogans, could result in a PR nightmare and an even higher risk of consumer backlash.

Finally, it’s highly unlikely that other operators in the services industry are going to follow the airlines’ incremental fees practice at a similar level of measurability. For the exact reasons I outlined in the first section – based on cost control, they do not need to.

It is largely an airline and air transport-specific trend. It’s a catch-22: air travel has gone from being an exclusive good to a commonplace product. However, on the plus side, you can expect to pay less for a round-trip ticket in September 2013 than you might have in September 1993.