The Economist had an interesting article in the July 11th issue on the hidden cost of price comparison websites (see “Free exchange: Costly comparison“). In theory, such sites should lower prices. When you have perfect knowledge of the prices multiple vendors charge for the same product, all vendors should race to the bottom. That’s why you can search for the same flight on the sites of online travel agencies or on the airline’s own website and see the same price quoted. Even slightly dissimilar goods that are otherwise alike may be priced the same — think of different airlines offering service between two cities, but with different schedules and connections.

Small inconveniences in price comparison,can be enough to let some competitors charge higher prices. Hotels may contract with an online travel agency for one rate and match that rate on their own website, but they also publish other rates — both higher and lower — with different rules attached. You’ll have to visit a different website to find them. Or consider Southwest Airlines, which only lets customers search for its flights on its own website. As long as people have a reason to go to Southwest’s website — such as its reputation for good customer service and free checked bags — it can worry less about charging the same price as United, Delta, or American. I’m not saying its feel-good image wouldn’t continue to work in the face of direct competition. It would just work less well.

However, The Economist cites a recent study by David Ronayne of Warwick University that argues the commissions charged by these price comparison websites can result in higher prices for everyone.

It works on the same principle as credit card processing fees. Most merchants just roll those fees into the retail cost of their products as a business expense. This is unlikely to be an issue with travel as much of it is paid with credit cards. But when applying the same principle to commissions, it means that even people who book directly with the airline or hotel could end up subsidizing those who use a comparison website.

Many of you are already vaguely familiar with this problem. Hotel loyalty programs often don’t provide points or status when reservations are made with a third party. This is how they compensate for the commission: what ever value you could have received directly was instead given to the travel agency. That might be a fair trade when the travel agency actually offers a better price. In practice, everyone has pretty similar prices these days.

What the OTA offers is convenience, and that’s the irony. There are many OTAs, and they’re all competing with each other. They require merchants to sign agreements that they won’t offer lower prices elsewhere, and they have business expenses — including their own advertising and rewards programs — that require them to charge the hotels even more.

It sounded like a good idea when Expedia and Orbitz and the rest first appeared. Instead we now have more complexity, more layers of people each wanting to get their cut.

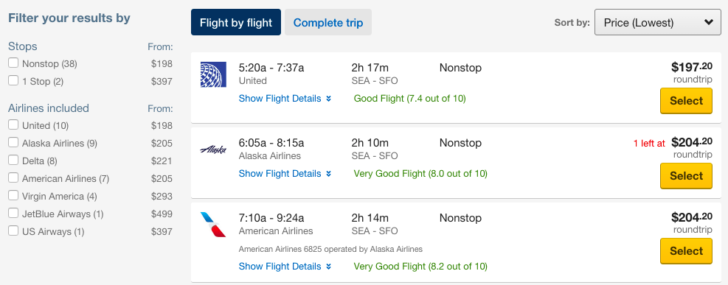

The “solution” from an academic perspective is to do your own research. If you do all your own price comparison shopping then you will have that perfect knowledge of the competitive environment necessary to pick the best option without giving the online travel agency its cut. But that takes time. Convenience is why these sites exist in the first place.

An alternative is to regulate cost comparison as a public utility. The Economist mentions the Affordable Care Act’s healthcare shopping websites and then reminds readers that good comparison sites are difficult to create. I’ve argued that ITA Matrix is similar in that it is unbiased because it doesn’t actually sell airfare — it’s a marketing tool to the airlines interested in buying ITA’s services. However, it also has reliability issues.

A third option not discussed in the article is to unbundle these fees from the purchase, to rebel against cost comparison websites and force users who choose to rely on them to pay for that convenience. Lufthansa plans to add a new 16 euro fee to tickets booked outside its own sales channels beginning September 1. I don’t imagine it will be long before hoteliers add a similar surcharge, much like a resort fee. Some of them are already introducing new benefits, including free Internet access, and restricting them to those who book directly.

Expect to see more changes like these in the future from both airlines and hotels as they seek to guide traffic back to their channels and offload commissions onto the customers who insist on shopping elsewhere.