I’m discussing airline inventory this week, including fare class availability, fares themselves, and fare construction. A lot of talk about fares for a product some people don’t think is priced very fairly at all. 😛 Now I know a lot of you are probably interested in award space, but this is purely a discussion of revenue travel right now. A lot of the same principles apply, so it it might be worth paying attention anyway.

When I introduced some of you to the concept of airline inventory, you learned why these companies have so many different inventory buckets even when everyone is sitting in the same cabin. You also learned how this concept can explain why the fare you’ve been watching suddenly doubled overnight.

The complement to the fare class is the fare itself, represented by a fare basis code of letters and numbers that identifies each unique fare. Just as an airline distributes all the seats for a particular flight into individual fare buckets well in advance of departure, it does something similar with the actual fares its customers will end up paying.

However, the separation between published fares and dynamic fare availability provides the airline with considerable flexibility when responding to supply and demand. Fares can be pulled and new ones published much more easily than changing the price of individual seats on each plane, and availability is largely determined by how many customers are buying and selling with inventory management getting involved only if it determines that the plane runs a serious risk of being under or oversold more than originally projected.

(Just in case any of you are confused by the letters I use below, I’m relying on my own experience with United. For the most part, this particular detail doesn’t matter.)

The Self-Run Airline

When most people are taught about supply and demand in their college economics courses, it’s in the context of a single item. If lots of people want that item, the price is raised. If not, the price is lowered. But this view is simplistic and impractical for a global airline. Even a small airline would have trouble monitoring every single flight to adjust prices in response to demand. And what happens if no one buys a seat for a few days? Should the airline cut the price? Then perhaps 20 people will buy tickets all at once before the price can be raised again.

Airlines need a system that can run by itself. Fare classes are an important part of this, dividing up the seats available for sale into several different buckets, each at a different price. The fare includes that price as well as a set of rules that tells you how you are allowed to get from A to B. Expect more on fare rules in a later post. Once an airline publishes a fare, it can leave it alone for several months, set an expiration date, or even pull it early if there was a mistake.

Just because an extremely cheep fare has been published doesn’t mean you can book it. If it requires availability in the G fare class and none is left, then you’re out of luck. Sometimes no deep-discount G seats are ever made available. This is a clever way to respond to expectations of high demand for certain flights, like those around Thanksgiving, by forcing people to by W fares or higher. No new fares have to be published or removed for prices to go up. Cheap fare class availability is just taken away.

Of course, none of this is to say that an airline’s inventory is truly self-run. Inventory management is one of the most secretive and important parts of any airline, making sure the company can get the maximum amount of money out of each passenger and ensure a profit at the end of the year. Airlines are not known as good investments, so this is no easy task. Don’t forget this quote from Richard Branson, owner of Virgin Atlantic (and everything else named “Virgin”):

What’s the quickest way to become a millionaire? Start off with a billion dollars and invest in an airline.

Taking Advantage of Published Fare Data

By searching for fares first you can determine the lowest possible price. Once you know the rules of that particular fare, then you can look for flights that mean those rules and also have availability in the required fare class. A calendar search on ITA isn’t necessarily the same thing. Sure, it will tell you that departing on the 23rd is cheaper than on the 17th, but it doesn’t tell you why.

Now that you’ve read about fare construction you know why, which means you can be more purposeful in your search. It’s also nice to know that even though ITA is telling you it will cost $973 to visit family for Christmas (my recent experience), that isn’t due to any mistake. That really could be the lowest fare that exists, so you can stop searching and just accept the hole about to form in your pocket. 🙁

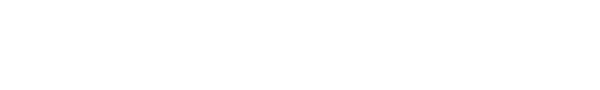

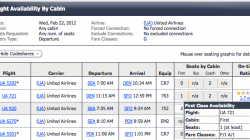

Here’s an example of a fare schedule from United Airlines that I obtained from KVS Tool. Similar data can be obtained from ExpertFlyer. It lists all the published fares for roundtrip travel between Seattle and San Francisco that are current through September [note: this screenshot is old and probably out-of-date].

Each of these fares has its own rules, of course, but this is a list of what is possible, and a fare construction expert can work from there to find out what can actually be booked. Note that several fare buckets (denoted by the first letter of the fare basis code) actually have multiple fares listed, sometimes for very comparable or identical prices. This is because they actually have somewhat different rules. Depending on what you actually try to book, you may find that you have to one fare instead of another even if they require the same availability.

For the dates I entered, prices range from $378 for an L fare to well over $3,000 for an unrestricted Y fare. That’s higher than I usually pay to fly to Baltimore, but this was taken far in advance before much discounting had occurred. At least I know when searching for a ticket that $378 is the lowest I can go if I want to stay on United.

Often when mistake fares are published, or if a carrier wants to raise prices on the weekends, or for whatever reason, it is pretty easy to just zero out availability in the lowest buckets without revoking the cheap fare. This is what I think is genius about airfares. It’s not like the carrier has to constantly monitor each flight to raise the price step-wise in response to supply and demand. It just has to determine and publish a wide range of fares that remain in effect for months at a time. Historical data then allows it to predict how many of each fare will actually get sold.

If demand is especially high for an individual flight, it can limit access to the cheaper fares by manually reducing availability in certain buckets. If demand is low, it opens it back up. In the case of sales or a fare war between competing airlines, new fares might be published, but these usually exist for a short time before expiring.

I used an analogy of pricing food in advance at a grocery store I introduced fare classes. To represent fares with another imperfect analogy, I would use a restaurant menu. The prices are published for each dish, and each dish has its required ingredients (fare classes). If one dish requires chicken, I can’t sell it to you if there isn’t any chicken, but I’m also not going to reprint all the menus, either. You can come back on a different night and see if I have chicken then.

Those diners who absolutely must eat tonight will have to settle for lobster and pay a much higher bill at the end of their meal. We call these people business travelers. 😉 Or the occasional family member who doesn’t plan ahead and calls me in a panic.

What about Fare Basis Codes?

I’m not planning at this point to spend much time explaining how to decipher fare basis codes, the unique string of letters and numbers that represent each fare. First of all, it’s boring. And second, I’m not sure how useful it really is unless you’re looking for something specific. Me, I just look for what’s cheapest and move up from there if for some reason the rules don’t fit my needs. I usually work around the deals rather than put in the effort to make the fares fit my budget and schedule. Although I like maximizing miles and things like that, my patience wears thin faster than some other mileage runners.

If you want to learn more, Darren has a good post at his blog, Frequently Flying, that may be able to help you out. But to be helpful, I’ll give you a summary. As you can see in his screenshot from FareCompare, there are lots of different fare basis codes with a range of character lengths. That’s because the code itself actually tells you something about the specific fare rules within. The first character is going to be the fare class, so in Darren’s example of GA14CS from United, that means it is a G fare, the lowest-discounted economy fare class.

Sometimes you’ll get a second letter. In this case that’s “A” and indicates this is a oneway fare. Darren recommends these as a good indicator of a potential mileage run candidate. Booking one-ways, even for normal travel, is a great way to mix and match your outbound and return flights in certain situations. (There is a growing trend to price roundtrips the same as two one-ways, so the theory that you need a roundtrip ticket to save money isn’t always correct. Although if you need to cancel, you risk paying two cancellation fees if you have separate tickets.)

Also, sometimes you’ll see some numbers. These are almost always a multiple of 7 and indicate the advance purchase requirement. Deadlines of 7, 14, or 21 days are most common. Longer number strings like “143″ mean a 14 day advance purchase requirement in addition to a 3-night minimum stay. Other letters in the code may indicate time restrictions (e.g., you can only travel during off-hours) or that this is a non-refundable fare. International fares are more complicated to decode, but again, this is an advanced topic that does not concern most people.

Is your head spinning yet? Next time I’ll discuss the language of fare rules. Like any other kind of legalese, hopefully you’ll find it’s not that hard once you understand the definitions and have the patience to work out the logic.