Continuing last week’s introduction to ExpertFlyer, today I’ll discuss different ways to combine fares and flights using what are called “pricing units.” There are a lot of terms here, but they aren’t too important. You should still come away with a better sense of how fares are combined so that you can understand what the fare rules mean when they say “combinations permitted.” You may want to read up on earlier installments to become familiar with the backstory:

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Fare Rules and Prices

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Finding Availability and Constructing Fares

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: When Manual Fare Construction Helps or Hurts

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Combining Fares and Pricing Units

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Planning an Award Trip

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Routing Rules

One or More Fare Components Create an Itinerary

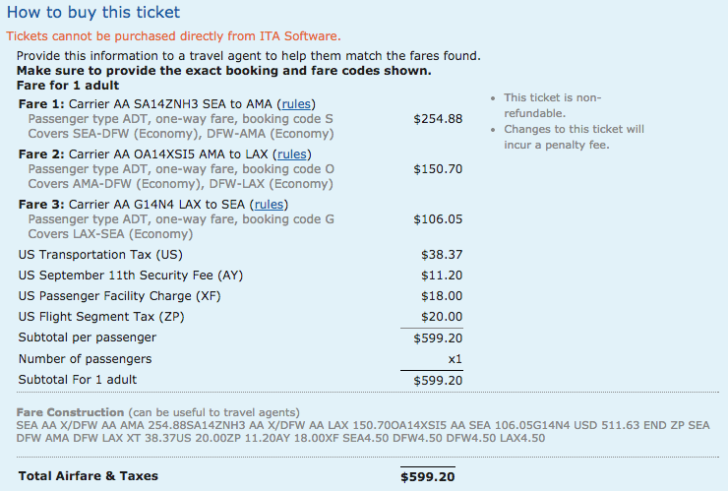

A single ticket is limited to 16 flights, but those flights can be covered by different fares. Remember the example I gave of my potential trip from Seattle to Amarillo? There were three fare components — three fares — used in that itinerary.

- Fare 1 (AA SA14ZNH3) covered two flights: Seattle-Dallas and Dallas-Amarillo. The fare component covered the entire trip Seattle to Amarillo but permitted a connection.

- Fare 2 (AA OA14XSI5) covered two flights: Amarillo-Dallas and Dallas-Los Angeles. The fare component covered the entire trip from Amarillo to Los Angeles but permitted a connection.

- Fare 3 (AA G14N4) covered one flight: Los Angeles-Seattle. This fare component didn’t need a connection, though it did permit up to three.

- And of course, all three fares permitted their combination with the others.

Add up the fares along with their accompanying fees and taxes and you can get the total price. Sometimes you’ll find a single fare that will let you book the same flights. But in this particular case, that single fare was about $650. By combining multiple fare components I got to book the same ticket at a lower total price. Most travel search engines do this automatically, comparing not just which fare is cheapest but also which combination of fares is cheapest.

Fare Components Are Combined to Form Pricing Units

Although you are allowed to combine multiple fares, there are still more rules that determine exactly how you do it. For example, here is the relevant section from the fare rules for AA G14N4 that I mentioned above:

DOUBLE OPEN JAWS NOT PERMITTED.

OPEN JAWS/2-COMPONENT CIRCLE TRIPS/MULTI-COMPONENT

CIRCLE TRIPS/END-ON-END

FARES MAY BE COMBINED ON A HALF ROUND TRIP BASIS

-TO FORM SINGLE OPEN JAWS

A MAXIMUM OF 2 STOPOVERS PERMITTED AT FARE BREAK

POINTS. MILEAGE OF THE OPEN SEGMENT MUST BE EQUAL/

LESS THAN MILEAGE OF THE SHORTEST FLOWN FARE

COMPONENT.

-TO FORM 2-COMPONENT CIRCLE TRIPS

-TO FORM MULTI-COMPONENT CIRCLE TRIPS WITH AA FARES

A MAXIMUM OF 2 STOPOVERS PERMITTED AT FARE BREAK

POINTS.

END-ON-END COMBINATIONS PERMITTED. VALIDATE ALL

FARE COMPONENTS. SIDE TRIPS PERMITTED WITH NO

RESTRICTIONS. TRAVEL MUST BE VIA THE POINT OF

COMBINATION.

PROVIDED –

COMBINATIONS ARE WITH ANY FARE FOR CARRIER AS IN

ANY RULE IN ANY TARIFF.

COMBINATIONS ARE WITH ANY FARE FOR ANY CARRIER

WITH ANY RULE IN ANY PUBLIC TARIFF.

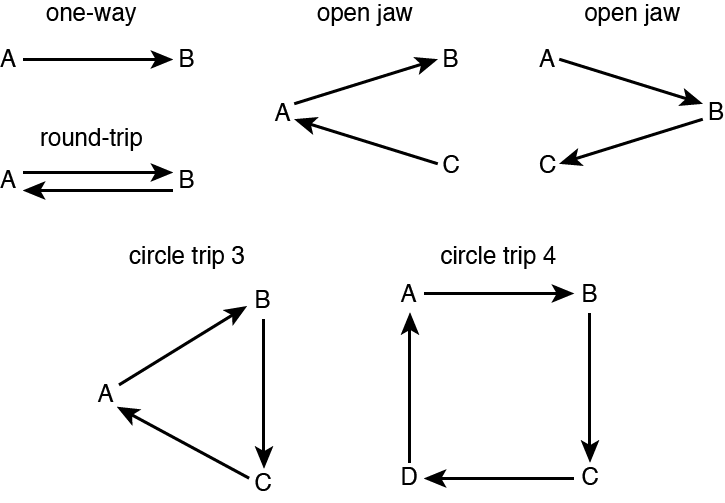

You may be familiar with open jaws, but others sound more complex. Here’s a guide:

Just like there can be more than one fare, there can also be more than one pricing unit in a single ticket, but all the fares have to fit into one of these templates. Sometimes there may be multiple fares but only one pricing unit. In the example of my trip to Amarillo, it was a circle trip 3, traveling from Seattle to Amarillo to Los Angeles and back to Seattle.

NOTE: Each of the arrows in the figure above represents a fare between two cities, not the actual flights. There may or may not be connections at additional cities. For example, in the circle trip example, the line from A —-> B represents the fare from Seattle to Amarillo. There is a connection in Dallas that is not represented here.

I can form one pricing unit like my trip to Amarillo and then combine it with another pricing unit on the same ticket. For example, I could include a one-way pricing unit from Seattle to Vancouver. But once you form a pricing unit, it isn’t always necessary that they line up in a row from one city to the next. I could combine it with a completely unrelated flight from Honolulu to Tokyo. I’m still adding a one-way pricing unit to the same ticket, but I didn’t include a journey from Seattle to Honolulu.

Applying Rules to Pricing Units

Many rules have references to pricing units and fare components, which I hope you now have a better chance of understanding. Take, for instance, many rules about stopovers. If the rules of a particular fare say “no stopovers on the pricing unit” that doesn’t mean you aren’t allowed any stopovers on the ticket. It just means not on that pricing unit. Maybe the Honolulu-Tokyo pricing unit I mentioned above doesn’t allow stopovers but the fares that make up my circle trip to Amarillo do allow them.

A more familiar example is the Saturday night stay requirement, typically used to prevent business travelers from booking inexpensive fares (because they wouldn’t want to stay all weekend at their destination). The rules might say “Saturday night stay required on the first fare component of the first pricing unit.” Go back to my circle trip to Amarillo and imagine this rule applied. I would need to spend a Saturday night in Amarillo because my first fare component took me to Amarillo. My second fare component takes me to Los Angeles, but I don’t need to spend a Saturday night anymore. I can continue immediately on the third fare component to Seattle. And if I happened to combine it with another pricing unit, like that one-way trip to Vancouver (or to Tokyo), then the Saturday night stay wouldn’t apply there, either, because it is the first fare component of the second pricing unit.

Are you getting dizzy yet?