In yesterday’s post I reviewed the basics of searching for airline fares. Today I will use that fare information and match it with the booking class availability on different flights. I strongly recommend you read yesterday’s post so you can pick up where we left off. Otherwise not much will make sense.

Other posts in this series:

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Fare Rules and Prices

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Finding Availability and Constructing Fares

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: When Manual Fare Construction Helps or Hurts

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Combining Fares and Pricing Units

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Planning an Award Trip

- Introduction to ExpertFlyer: Routing Rules

Airlines Separate Their Prices from Actual Inventory

Airlines are free to change availability and fares independently, and doing so makes it easy to make broad changes without losing fine control over individual flights. For example, an airline can always choose to publish new fares or pull existing fares — even when they haven’t reached their expiration date. Or it may remove inventory from flights so that, while a low fare is still published, it can’t be used to book anything.

All the seats available on a plane are sorted into different booking classes (also called “fare classes” or “buckets”). The booking class must match the fare being used. Absent intervention from the, some booking classes will eventually sell out and customers will need to buy more expensive fares. Cheaper fares may be published, but those cheaper fares can only be used on other flights that haven’t sold out.

Booking classes themselves don’t have a price, though you’ll see them ranked in a way that usually goes from most expensive to cheapest. The first class fares are listed first, then the business class, and then the economy class. Within each of those cabin classes fares are sorted again based on the flexibility of their fare rules. Most carriers assign a fully flexible economy class ticket to the “Y” booking class and a fully flexible first class ticket to the “F” booking class. The letters used for discounted or less flexible fares within each cabin are more likely to vary between airlines.

You Rarely Get to See “True” Inventory

Finally, know that airlines don’t list the complete inventory in every booking class. For example, American Airlines stops counting at 7, and United Airlines stops counting at 9. There may be 15 tickets for sale in that booking class, but you’re only going to see 7 or 9. These booking classes can also overlap or be greater than the number of seats on a plane. The first class cabin on a domestic flight may have 7 tickets remaining in the F booking class and 5 tickets remaining in the discounted P booking class — but there are only 7 seats left, not 12. The fully flexible fare tends to represent total availability while discounted booking classes are a subset. If someone were to book a discounted P fare, then the availability in the F and P classes would both decrease, to 6 and 4.

Looking at inventory as a consumer is a little like looking at a picture of a ball. You know it’s round, but all you see is a flat circle. Only the airline sees every dimension and knows exactly how many tickets are available. But generally you don’t need to know any more in order to book a ticket.

Matching Availability to a Published Fare

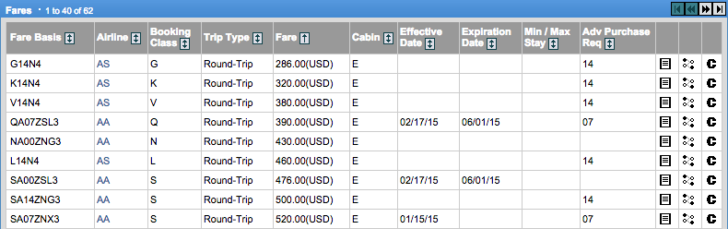

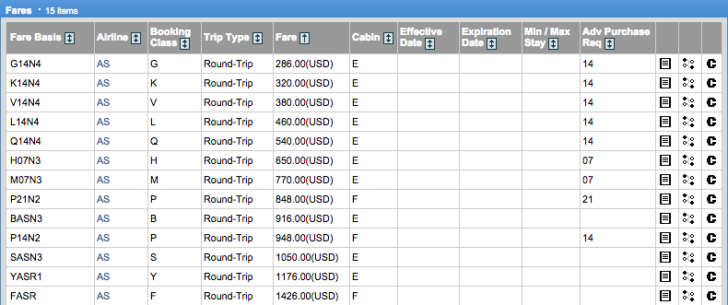

There were many different fares available for a weekend trip from Seattle to Austin in yesterday’s post. The absolute lowest price was offered by Frontier Airlines for $220 round-trip. However, I prefer to fly on American or Alaska Airlines because I value their frequent flyer benefits more highly; paying a little extra may be worth it if it means I get an upgrade. Narrowing the results to those two carriers I found that the cheapest fare was on Alaska Airlines for $286 round-trip and requires availability in the G booking class.

There was nothing unusual in the fare rules to suggest I had to be careful with the dates and duration of my trip. In fact, I asked ExpertFlyer to validate the fare when I performed my search, meaning it only returned results that would be valid for the dates that I had provided. (Technically, cheaper fares might be published, but if they are then I can’t use them anyway for reasons like blackout dates, etc. $286 is the cheapest fare Alaska offers for these particular dates.)

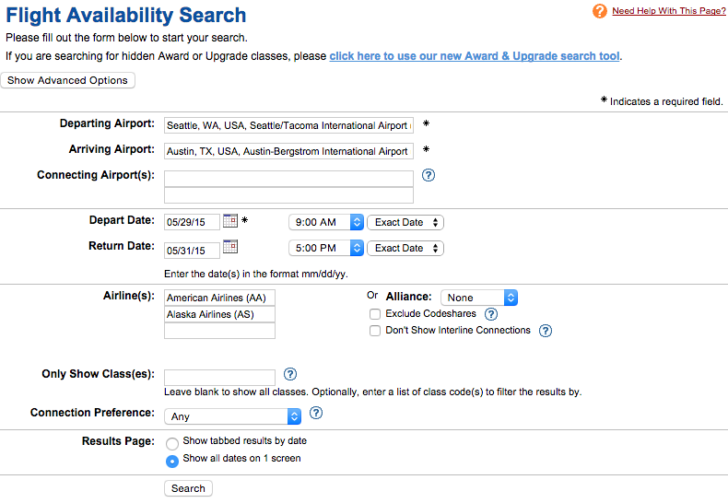

After finding a fare I liked, I performed a new search using the “Flight Availability” tool on ExpertFlyer. I searched for American Airlines and Alaska Airlines availability on the same dates that I used when searching these two airlines for published fares.

While there aren’t many options to worry about, I think it is important to specify your departure time when searching for availability. ExpertFlyer only returns about six results per day. If you leave it at the default setting (12:00 AM) then you will find that almost all results involve early morning departures. It’s a wasted search if you don’t want to leave so early. If a connection is permitted, it’s possible that all of the results will have the same early initial segment but different connecting segments. So be proactive and specify a preferred departure time.

Sometimes the Availability You Want Doesn’t Exist

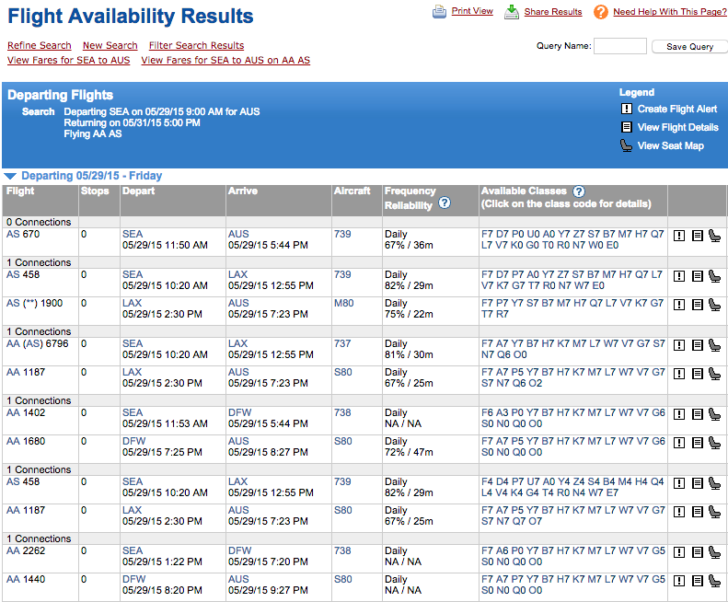

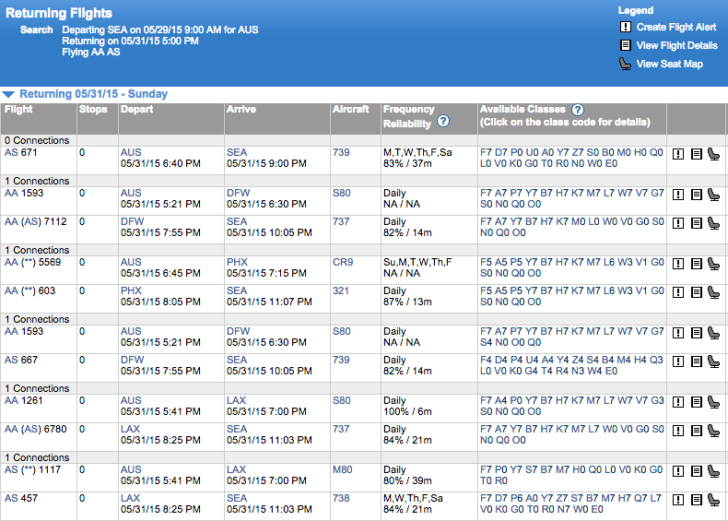

The cheap fare that I’m interested in is available on a connecting flight from Seattle through Los Angeles (G7 on both AS458 and AS1900), but I’m really more interested in the non-stop flight AS670. That particular flight does not have any availability in the G booking class. The lowest class available is V, which has 7 (or more) tickets for sale. Going back to the first figure, Alaska Airlines has a V fare for $380 round-trip, nearly $100 more than the G fare I originally looked for. To make matters worse, the returning nonstop flight only has availability in first class and Y (Z is an award bucket that we should ignore for this exercise).

To give you a better sense of what we’re working with, I repeated the fare search in the first figure to show all the fares published by Alaska Airlines (and validated for these dates). While American could offer a codeshare, a casual examination suggests that most of American’s fares are higher than Alaska’s. We’ll focus on matching Alaska fares to Alaska flights and discuss codeshares later this week.

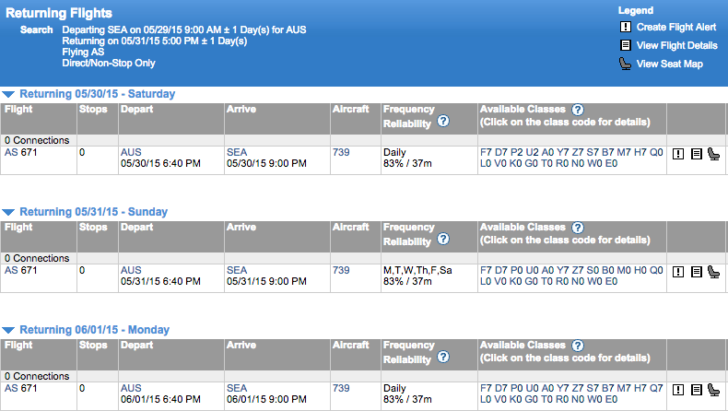

I’m stuck because there is no G availability. So what do I do? I want the nonstop flight, but I’m not going to get it for as cheap as I would have liked. I’ll repeat my search on adjacent days to see if I can return on a different date when there is better availability in cheaper booking classes. This is done by selecting the “+/- 1 day” option from the menu next to my return date. (I also selected “non-stop” from the connection preference menu. Assuming there aren’t too many flights, it’s easier to view them all on one page instead of different tabs.)

You can see here that availability is better on Saturday and Monday, but Monday is the preferable choice. The lowest booking class available on Saturday is H ($650 round-trip), while on Monday the lowest booking class available is Q ($540 round-trip). I’ll pick Monday’s flight.

It’s okay that I’m traveling outbound on a V fare and returning on a Q fare. The rules of these two fares specifically permit combining with other fares for one-way travel at half the round-trip price, which I discussed at the end of yesterday’s post.

Important Tip: If either fare prohibited this kind of combination, then I might have to buy a more expensive fare that allowed it. In other words, there might be a very cheap fare in at least one direction, but if the that cheaper fare prevented such combinations then I would need to pass over it and buy a more expensive one. The most restrictive rules win.

Pricing the Fare

To re-cap, I found a cheap fare but no flights with the right availability to book it. Instead I’ll have to settle for a more expensive fare. I can still save some money by combining two different fares: an expensive Q fare on the return, but a slightly less expensive V fare on the outbound. This is better than buying a Q fare in both directions. My cost should be close to the average of these two fares.

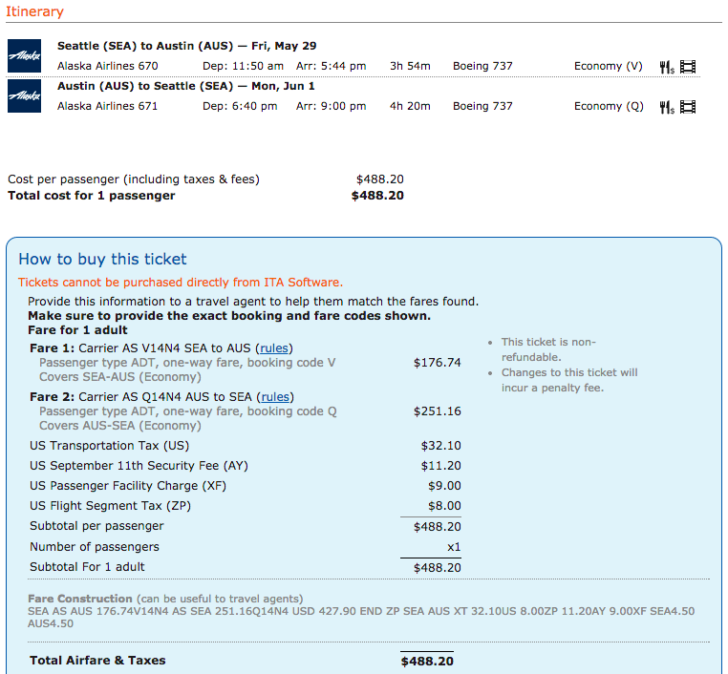

I can now confirm the price of the itinerary by going to ITA Matrix. I’ll search for the same dates — departing May 29 and returning June 1 (my new return date) — and pick the same flights on which I found availability on the non-stop flights. ITA Matrix doesn’t sell flights, but on the final page I examine the computer’s fare construction and match its final price to my own calculations.

You can see the total price is $488.20. It’s a combination of one-half the V14N4 fare for $176.74 and one-half the Q14N4 fare for $251.16. These are roughly half the prices listed by ExpertFlyer for a round-trip ticket and indicate I did my job correctly.

The “Fare Construction” details in grey at the bottom of the page would be useful if you need to talk to a travel agent for help booking this fare, but the most important part is the fare basis codes. So far I have never had to go to a travel agent for help. Just sayin’.

Why Is ITA’s Price Only “Roughly” the Same?

Published fares include some taxes and fees, but not all of them. International fares are a good example and would likely also have fuel surcharges of several hundred dollars that are not listed in the published base fares.

But it’s not hard to find out where the extra money went. Take half of fare V14N4 ($380/2 = $190) and half of fare Q14N4 ($540/2 = $270). The total would be just $460. The extra $28.20 comes from the September 11 security fee, the passenger facility charge, and the flight segment tax. Once you include those, the numbers add up. It’s not meant as deception — these extras just aren’t published as part of the fare (and for good reason: it can be difficult to determine some fees until you know how many or which airports you’ll be passing through).

I hope you recognize the significance of what I did here. I didn’t tell ITA Matrix to search for a specific fare. I just asked it to look for the cheapest options on those dates and chose the same flights on which I knew there was a certain amount of availability. The price it found matched the price I found manually, proving that a human can do fare construction as well as a computer.

What’s the Point?

Tomorrow I’ll show that computers are sometimes better than humans, and also explain why humans are sometimes better than computers. Learning to do your own fare construction is a valuable skill even when ITA Matrix can come up with the same result in much less time. A lot of it has to do with just how much you trust the computer to do its job correctly. And other applications, like building an itinerary for award travel, are not nearly as well automated.