To the surprise of few, struggling Australian flag carrier Qantas Airways continues to post unimpressive earnings month after month. The Sydney-based airline posted a net loss of A$244 million (US $256 million) for the fiscal year ending 30 June 2012, compared to a net profit of A$250 during the same period a year prior.

The global airline industry continues to struggle as a whole, particularly the larger legacy network carriers such as Qantas which carry the burden of higher cost structures than newer low-cost entrants. However, it seems that many big name carriers such as American Airlines, Air France-KLM, and Air India, for example, are suffering due to a multitude of problems: labor unrest, rising operating costs, aging fleet, fuel prices, outdated in-flight product offering, low employee morale, etc.

However, there are also plenty of struggling carriers that can tie their biggest challenges back to a general, over-arching bottle neck which continues to drag down overall financial and operational performance. Chicago-based United Airlines has literally become the laughing stock of the industry after being crippled by system malfunctions time after time again since migrating to a new IT platform in March. The world’s largest carrier merged with Continental Airlines in 2010, and while the management of the combined carrier chose to retain the name “United” for the new airline, they decided to integrate both carriers onto Continental’s IT system known as SHARES. The end results have been nightmarish for United as computer glitches continue to plague the carrier 6 months post-implementation, inconveniencing thousands of passengers and showing marginal signs of improvement.

Qantas, meanwhile, has isolated its number one challenge: the highly unprofitable international network.

The complexity behind network planning is really not as cut-and-dry as one might envision. Retain routes that make money, ax those that don’t. Carriers with very lean cost structures, such as Spirit, RyanAir and Allegiant, will quickly abandon routes that don’t produce money rather than allow the market to develop. Other carriers that command higher profit margins, such as Singapore Airlines, can conversely sustain so-called “glamour routes” such as the ultra-long haul (and expensive to operate) nonstop flights between Newark and Singapore or Los Angeles and Singapore, even if they may not break even.

The truth is, it involves more strategic planning than that. Too many network adjustments and restructures can lead to unraveling the entire system as a whole. Many airlines, particularly those who build their network models around the hub-and-spoke system, design routes, deploy capacity and arrange schedules using precise economic modeling that seeks to capture upon traffic flows between various points. The situation becomes especially delicate for countries like Australia, where the nation faces two challenges as-is: one is population size, in which case Australia itself is not by and large catering to the same amount of traffic levels as China, Brazil, India, etc. and two is geographic positioning, which obviously doesn’t serve as an advantage given that the country is located very far south. Poor geography leads to longer stage lengths for long-haul flights, which becomes costlier to operate given fuel prices, crew expenditures, aging fleet and maintenance.

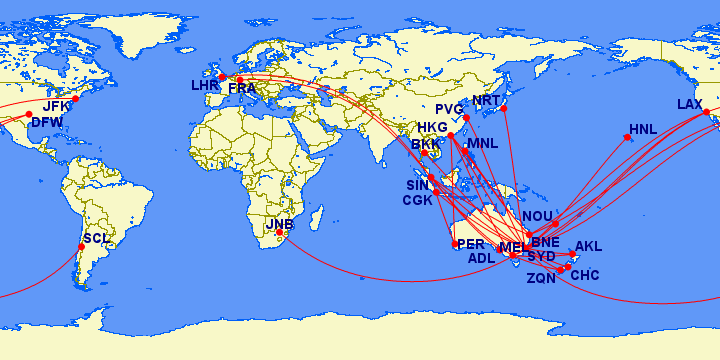

Such challenges only become compounded when factoring in the rest of the competitive landscape. Qantas once operated a fairly robust long-haul network connecting large cities in Europe – such as Amsterdam, Paris, Madrid, Manchester, and Athens – to down under through “scissor hub” operations located midway in Bangkok, Hong Kong and Singapore. However, the rise of Gulf Coast carriers such as Emirates Airline and Etihad Airways, based in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, respectively, have forced Qantas to reduce its European network down to two cities: London Heathrow airport (LHR) and Frankfurt Main airport (FRA) in Germany.

Across other regions, Qantas has also dropped nonstop services to India, Argentina, Canada, Turkey, Mexico, Malaysia, South Korea and scaled back significantly in China, Japan, and the United States. Some of these routes have been supplemented by Qantas’ low-cost subsidiary, Jetstar, launched in the early 2000’s, which has taken over many of its former loss-making routes in the short-haul and medium-haul sector. Jetstar has followed the low-cost, ancillary revenue model and has been very successful since its launch.

Interestingly, the one region that has been completely insulated from further shrinking has been Qantas’ domestic Australian network, which is actually highly profitable. Earlier this year, Qantas split its operations into two autonomous companies between the domestic and international sectors in an effort to bring its loss-making long-haul network into focus.

The fact remains that Qantas has found itself in a difficult position, invariably backed into a corner, if you will, in terms of devising a sustainable turnaround plan to revive its international operations. The scale back in Europe is particularly notable in that Qantas is now serving merely two destinations in the entire region on its own metal: one on continental Europe and the other in the British Isles. Qantas has a joint-revenue sharing agreement with fellow OneWorld partner British Airways, which is based at Heathrow, and the so-called “Kangaroo Route” between Australia and London Heathrow is supposed to be its main artery to connect traffic between Europe and Oceania.

However, this strategy faces severe limitations in that it requires often two or more connections for travelers between these points. The flight to and from London has to make a fueling stopover in Singapore before continuing on to Australian gateways at Perth, Melbourne, Brisbane or Sydney. Passengers originating or terminating in European points other than London have to deal with the hassle of back-tracking through the congested Heathrow airport, which is actually a nightmare given that Qantas and British Airways are housed in separate terminals.

Within Asia, Qantas has stayed in key important cities such as Tokyo, Hong Kong, Manila, Shanghai, Singapore, Bangkok and Jakarta. Elsewhere, much of the flying has been outsourced to its Jetstar operations. In North America, Qantas has long maintained its presence on the lucrative Los Angeles to Australia corridor, as it was one of the first cities in the Qantas network to receive the jumbo Airbus A380-800 series aircraft when it was delivered to the carrier in 2008.

More recently, Qantas has also tapped into fellow OneWorld hubs in the rest of the Americas by offering nonstop servies to Dallas/Ft. Worth Intentional airport (DFW) and Santiago de Chileairport (SCL), both of which are home to partners American Airlines and LAN Airlines, respectively.

Qantas’ International Operations as of 31-Aug-12.

Qantas’ International Operations as of 31-Aug-12.

Over the summer, it had been highly rumored that Qantas was seeking to ink a deal with Emirates Airline in Dubai in order to save its international operations. The alliance partnership would entail a code-share agreement between the two carriers and route swaps giving Emirates the majority of control on routes to Europe from its Dubai hub, which would connect to a “shuttle series” of up to eight Airbus A380 super jumbos flying onward from Dubai to Australia. The reciprocal benefits would include giving Qantas access to a wider portfolio of destinations across Europe, which Emirates already serves nonstop from Dubai, and providing Emirates access to Qantas lucrative frequent flier base and program.

This morning, the Sydney Morning Herald confirmed that the carriers are expected to announce the deal by sometime next week.

It has left a lot of people scratching their heads, wondering if this is indeed a wise move by Qantas or simply a short-term Hail Mary move by Qantas Management under severe pressure to negotiate a deal. Earlier this year, Qantas efforts to establish an all-premium airline called RedQ in Southeast Asia fell through after talks with Malaysia Airlines in Kuala Lumpur, and Qantas management came out of that situation looking not-so-good.

One of the biggest puzzle pieces is that Qantas is one of the founding members of the OneWorld alliance – and has deep ties with British Airways, also known as a huge rival of Emirates. The long-standing joint services agreement between British Airways and Qantas on the Kangaroo Routes could inevitably be put in jeopardy with the Qantas-Emirates tie-up.

Moreover, it could also be viewed as a move of capitulation: rather than conduct an internal reflection on how to raise its standards in order to win back customers, Qantas is surrendering at the hands of the enemy. Some people have even gone further to say that this will be the slow-death of the airline. It is rumored that the airline will drop its Frankfurt route, the sole remaining destination on mainland Europe, and keep London as the surviving European destination served on Qantas metal.

It is important to remember that this is simply ONE region of Qantas’ network that is seeking the international fix. Emirates will not be filling in any needs on Qantas’ Asian, North American/Latin American and South Pacific arms, which are decent performers for Qantas. It is the European network that needs the most fixing, and provides the lowest-yielding returns of all of Qantas’ routes.

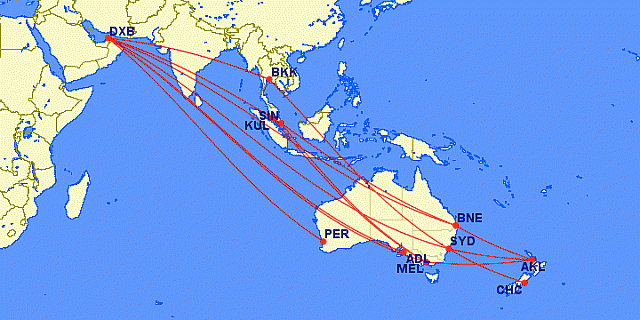

At present, there are three carriers flying nonstop between the United Arab Emirates and Australia: Emirates, Etihad and Virgin Australia. Emirates dominates the market share at roughly three-quarters of the weekly seating capacity.

Emirates route map to Australia and New Zealand from Dubai (note: Adelaide is expected to begin services in November 2012).

Emirates route map to Australia and New Zealand from Dubai (note: Adelaide is expected to begin services in November 2012).

While Emirates faces limitations in the Australian market due to bilateral restrictions between the UAE and Australia, the carrier has overall managed to find great success in capturing a lucrative share of the passenger traffic. As such, it brings into question why Qantas wants to establish a virtual “hub” in Dubai when Emirates appears already fairly entrenched in the Australian market as-is. On the flip-side of that argument, once Emirates maxes out the number of weekly frequencies it is allotted in Australia, it may need to leverage the profitable Qantas domestic network in order to expand its presence.

Moreover, will the Emirates partnership be enough to stem further losses? Qantas executives point out that Asia is the high-growth market where the airline needs to increase its presence. But, is Qantas capable of finding demand for a full-service carrier in those sectors? Furthermore, can its hubs generate the traffic feed needed to sustain such routes over the long term?

The Jetstar brand has been successful in its Asian expansion efforts, as it has an international network with focuses in Japan, Asia and hopefully soon Hong Kong. But, then again, that doesn’t seem to solve the challenge that plagues Qantas international. If the Qantas Group continues to invest in Jetstar, then that leaves little opportunity for Qantas to capitalize on without running the risk of cannibalization.

In summary, this could be one of the most effective moves in Qantas history on part of its senior management, or one that shoots the carrier in the foot. It may simply be difficult for people to accept the fact that Qantas may never be able to compete again in the global realm on its own metal. Times have changed and the network has had to adapt accordingly.

Whatever the solution may be, time is not on Qantas’ side. Opening up Europe via Emirates is potentially a good step in the right direction, but it will still face limitations and potential hurdles. Let’s see if both carriers can leverage their strengths and brands to provide mutual benefits moving forward.