Headquarters and Leadership:

The Service Oversight Center (SOC) and Headquarters will be located in Fort Worth, TX, the present home of AMR Corporation (the parent company of American Airlines). US Airways’ SOC is currently located in Pittsburgh, PA, but its headquarters is in Tempe, AZ. American’s current Chairman and CEO, Thomas Horton, will serve as Chairman of the combined airlines’ Board of Directors through its first annual meeting of shareholders, and will serve as the combined airlines’ representative of the OneWorld global alliance. The Board will be comprised of three American Airlines representatives, including Horton, four US Airways representatives, including Doug Parker, and five AMR creditor representatives.

Livery, logo and paint scheme:

The US Airways name will disappear and the merged entity will retain American’s name. American’s controversial new livery, which was unveiled on January 17, 2013, will (unfortunately) remain in place. It is inconceivable to think that the airline would spend millions on a re-branding campaign and scrap its plans within 30 days due to merger activity. The re-branding decision, and resulting hideous paint scheme, was debuted entirely with a US Airways merger in mind. AA claims that the re-branding effort began before the carrier filed for bankruptcy in 2011, and that US Airways played no role in the re-branding process. I don’t dispute this, personally, but I also don’t think US was a complete afterthought, either. Regardless, it’s a legitimate excuse for American to get away with this hair-brained idea over the long-run, and in the four weeks that has elapsed since the new logo and paint scheme became publicly known, I still haven’t shifted my stance on the issue.

Fleet

One thing that mergers inevitably breed is a mashing of fleet types across Boeing and Airbus models, as was the case for both Delta Air Lines when it merged with Northwest Airlines in 2008 and United with Continental Airlines in 2010. US Airways and American will be no different, as both airlines either presently operate or expect to receive large deliveries from both major providers.

Widebody: American recieved its first Boeing 777-300ER series aircraft last month, which will remain the largest aircraft in the combined fleet and be deployed to capacity-restricted, important business markets such as London, São Paulo and Tokyo, likely from the pre-merger AA hubs only. American’s current 777-2ooER series planes are being re-configured with new Business Class and Main Cabin Extra seats, with First Class eliminated entirely, and these frames will likely be deployed on legacy US Airways and American routes to Europe, Latin America and Asia, such as Madrid, Beijing and Buenos Aires. Similar seating arrangements will take place on US Airways’ Airbus A330-300/200 series planes, and these frames will likely be used on more leisure-oriented routes to cities such as Roma and Barcelona

Both airlines operate fuel-inefficient Boeing 767-200ER series planes, although AA uses theirs primarily on domestic/transcontinental routes, whereas US deploys them internationally. Both carriers will likely see the retirement time frame for these aircraft moved up a bit as new Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 deliveries come in (hopefully). American’s 767-300ERs will remain in the fleet for some time, but will be re-fitted with fully lie-flat premium seating similar to those used on US Airways’ International Envoy service on the A330s.

Narrowbody: US and American both also operate 757s on a few transatlantic and medium-haul routes to Latin America and Hawaii, which will also see their replacement imminent as AA has A321 airframes on order to operate its transcontinental routes from JFK to SFO and LAX. If the combined carrier decides to continue using 757s on transatlantic routes, such as Philadelphia to Amsterdam, Charlotte to Dublin, etc, the American Airlines version will prevail over the model used by US, as it offers lie-flat seating and and upgraded interior product.

US’ 737-400 and AA’s MD-80 planes will see their retirement accelerated in favor of AA and US leveraging the 737-800 and Airbus A320 family planes on domestic short-haul routes.

Regional: American’s E-Jet orders will be a huge boon for the O’Hare hub, which is desperately in need of 100-seater planes with a more competitive product. US also brings a healthy number of E-Jets to the table, and the first pickings of these planes will go to the business-heavy hubs in the Northeast (PHL/WAS/NYC) and Chicago in the Midwest. This will relieve some of these hubs of Canadair Regional Jets, particularly at O’Hare, which can be re-deployed to the more geographically dispersed hubs on the coastal regions, such as CLT, MIA and LAX, or down to DFW.

One wildcard remains: US Airways Express’ Dash-8s. These are older aircraft that aren’t necessarily useless, and AA also has a few ATR-72 turboprop planes lying around. It’s possible the merged airline can order some more ATRs or Q400s to serve some secondary and tertiary cities in far-flung corners.

Network hubs and routes:

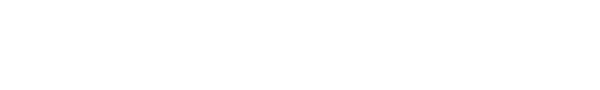

American currently has five major “cornerstone” hubs at Dallas/Ft. Worth, Chicago, Miami, New York and Los Angeles airports.

US Airways has three primary hubs at Phoenix, Philadelphia and Charlotte, and a smaller focus operation in Washington, D.C.

The good news for frequent fliers is that most of the current levels of operations across all nine of these affected hubs are likely to remain intact. While the two airlines do not compete directly on many flights from a route-by-route basis (hence, why the merger is likely not subject to any Department of Transportation anti-trust violations) there is still a fair amount of “regional” overlap that will result in some overall network trimming.

Let’s start in the east and move westward: American’s Miami hub is a Latin American gold mine, and will remain that way after the merger given the large amount of high-yielding Origin and Destination (O&D) traffic in the South Florida metropolitan area. Traffic levels to Latin America are booming these days, and the region has remained largely unaffected by premium revenue downturns that have crippled the transatlantic and transpacific long haul markets. Despite a large low-cost carrier presence at nearby Fort Lauderdale airport, American continues to rake in high profit margins at its Miami hub, which is a success story likely to play dividends for a long time.

Charlotte plays a strategically important role in covering the Southeastern US, and therefore will also likely see little impact. Charlotte also benefits from its own fare share of high-yielding traffic thanks to its banking/finance sector ties. Likely, some of Charlotte’s Caribbean and long-haul Europe/Latin American network may be reduced slightly as the more lucrative traffic can be routed through Miami, but it will retain key international linkages to cities like London, Frankfurt, Paris, and beach/island resort destinations in the Bahamas, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Netherlands Antilles, etc.

The New York/Philadelphia/Washington regions will also see minimal changes. Both JFK and LGA airports, where AA has sizable presences, are slot-restricted airports that can be now utilized more effectively for O&D traffic to strong domestic business markets (from LaGuardia to say Kansas City, Denver, and New Orleans) and important global destinations from JFK (such as Frankfurt, Moscow and Tel Aviv). Philadelphia, at present, has a robust transatlantic network via US Airways, and will likely retain those nonstop flights in becoming the singular, northeastern US connecting hub and gateway to Europe, and possibly receive a long-coveted nonstop flight to Tokyo finally. Washington National airport, also slot-restricted, will simply beef up its current “shuttle-like” operations to business markets like Chicago, Miami and Dallas/Ft. Worth.

American’s Chicago O’Hare hub has invariably suffered over the years to its #1 competitor, United, a much larger force in the same town. Schedules have been parred and mainline capacity has been shifted over to regional jets. Moreover, once considered AA’s primary gateway to Europe, Chicago has lost nonstop transatlantic services to cities such as Frankfurt, Zurich and Brussels. However, the merger will reverse much of those changes as American-US will have a new supply of “right-sized” aircraft with the optimal mix of seats to re-launch flights to markets in the Northeastern US (such as Providence, Rochester, Buffalo) and West Coast (Portland, Sacramento) that have either lost nonstop service to Chicago or experienced schedule and seat reductions. European flights will likely grow in smaller increments (AA is adding a year-round daily flight to Dusseldorf, Germany this summer) since Philly will take over the European gateway role for AA over the long run.

American’s LAX and DFW hubs will likely see the smallest changes of all. At LAX, similar to NYC, American chases after O&D traffic, which will be unaffected by the merger. As is, LAX is a fragmented market between many domestic airlines, and there isn’t much room to grow nor contract. DFW primarily serves as an East-West, North-South connecting hub with international services to key OneWorld hubs (Tokyo, Sydney, Madrid and London), important business markets (Frankfurt, Seoul and São Paulo) and a slew of destinations in Canada, Mexico, Latin America and the Caribbean, all of which will remain untouched by the merger. DFW will only stand to lose a few frequencies to some of the Southeastern US cities that can be handled over Charlotte.

Finally, that leaves Phoenix, which is likely to be the biggest loser in the merger. At present, Phoenix is linked to 78 domestic cities, 10 Latin American markets, and 9 Canadian cities. As of this week, US Airways offers 3,516 weekly departures from Phoenix, and controls 46.8% of the total overall market share. With the merger, Phoenix will likely lose anywhere from 40-50%, if not more, of the number of seats, daily departures, frequencies and cities as its functionality as a hub will be overshadowed by Dallas/Ft. Worth and Chicago.

Although Phoenix has large population density, and a high-volume of O&D traffic, it is a low-yielding hub. US Airways can sustain it at present since the airline follows an extremely lean/low-cost model, but once it merges with American, the combined carrier will see its cost base rise. With a more bloated structure, the airline will be unable to support the same level of nonstops and frequencies out of its PHX hub without raising fares, which will result in hefty turnover to lower-priced options on other carriers such as Southwest (the #2 airline in Phoenix) and the airline will fall out of favor among locals. In a best-case scenario, Phoenix will be shrunk to serve 50 or so cities at max, with a few key Canadian, Mexican and Hawaiian markets retained.

Wildcard situation: AA may re-venture into some of its non-cornerstone hub/point-to-point routes from former hub cities (such as Boston, San Francisco and Raleigh-Durham) that it ceded to low-cost carriers such as jetBlue and Southwest Airlines because it could not compete at its high-cost level.

Frequent Flier Program and Alliance :

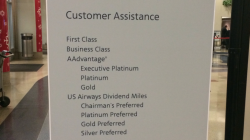

American’s AAdvantage Program is arguably the goose that laid the golden egg in terms of keeping AA alive in the post 9-11 world. It is revered by devout airline loyalists for providing the richest rewards with the highest level of elite treatment of all major US legacy carriers. US Airways uses a much more dieted elite program known as Dividend Miles.

American is a founder of the OneWorld alliance, and US Airways has been a member of Star Alliance since 2004. The merged airline will retain American’s AAdvantage program, and remain a member of OneWorld. US Airways has a pretty decent mileage accrual and redemption program with liberal allowances to accessing award tickets and benefits on United Airlines and other Star Alliance partner carriers, which will inevitably disappear in the near future. It is still unclear at which point US Airways will withdraw from Star Alliance and when reciprocal point accrual implementation will occur, as the merger is still subject to approval by the US Department of Transportation.

In-Flight Services:

Here is where things differ a bit, and where the combined carrier has the most to gain (or lose) in a perfect world. Put simply, the two airlines pursue fairly different business models when it comes to soft and hard products.

American has always targeted a much more premium-oriented passenger with higher service expectations. American provides free in-flight entertainment (IFE) on the majority of its domestic and long-haul flights, and has invested in technology “up-sells” over the years by offering Wi-Fi for sale on flights and also designed a sleek mobile application. Although many claim that American’s product has become stale and outdated over the years, the carrier has committed itself to drastic cabin overhauls to take place over the next few years by ordering new planes and installing personal TVs and Main Cabin Extra across its domestic mainline fleet. There are major incentives for providing extra services and frills as it will correlate to higher revenue figures, and AA is confident this will hold true moving forward.

In contrast, US Airways’ on-board product has more in common with low-cost carriers than legacy rivals. US Airways does not have a native mobile application (although it does have a mobile website that can still be used for online check-in and boarding pass scan) nor does it offer extra leg-room seating in coach and only provides IFE only on a select few of its international flights. While this strategy was permissible and practical for US Airways when it merged with America West Airlines in 2005, it will not be for its merger with American. US Airways is also using a very outdated website, whereas American has undergone several IT upgrades in various phases in recent months.

Issues with brand confusion are still problematic at the recently merged Delta and United. Some domestic flights offer in-flight wi-fi, personal entertainment screens and extra legroom cabins, while others do not. Fortunately for American, the product overhauls are still in their infancy stages and have not been implemented fleet-wide yet at a large scale, so standardizing the upgrades among both fleets is a bit more feasible in this situation.

Critical success factors

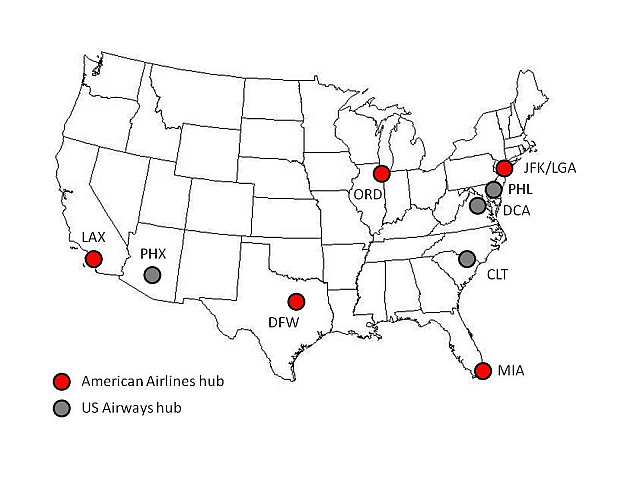

The disastrous United-Continental merger has taught the US airline industry many, many lessons about merger integration headaches, and what can be done to prevent them. Undeniably, airline mergers provide tremendous benefits in terms of enhanced network access and scheduling. They also may save an ailing airline that is devoid of a sustainable long-term strategic vision and remove it of labor challenges and financial burden.

However, those are merely tactical considerations that appear ideal on paper. In reality, it is all about overcoming the real murky areas that aren’t as easy to pin down.

The first crucial needs area revolves around nailing down a seamless distribution and technical platform migration strategy to support passenger reservations. The purported success of the United-Continental merger has been plagued by IT snarls after the two airlines migrated to HP’s SHARES software in March 2012, which was used by pre-merger Continental. System failures caused by poor preparation, repeated outages, insufficient training and lack of continued oversight and remedy has cost United dearly over the past year. Delays, cancellations, missing reservations and other grievances spawned competing carriers to offer status matches to United’s elite tier fliers, who have happily transferred their partisanship to other airlines and left Wall Street analysts badgering the empty-handed #1 airline about when it will achieve revenue parity with its competition.

That question has yet to be addressed.

American and US will face the same challenge as US Airways is currently operating on SHARES (allegedly the ‘low-cost leader’) and American uses Sabre’s reservation platform. No decisions have been made yet as to which system will prevail over the other, and likely will not be announced for several months. To add insult to injury, US Airways currently possesses two Single Operating Certificates, AWA and US, that has not been resolved since its last merger with America West Airlines. The upcoming merger will require unification between all three airlines (American, US and America West).

The next key component involves creating a frequent-flier program and product offering that is capable of retaining the elite fliers. Though a small batch of the overall flying public, these individuals churn out a disproportionately high level of the revenue and profits that land into the pockets of legacy airlines. Looking at numbers, for instance, a recent American Airlines executive said that 24% of their flyers comprise of 70% of their revenues. Losing as little as 1% of these loyalists can have drastic implications on the bottom line.

What is troublesome here is that looking at the same measurements for US Airways, the figures tell a different story: while it boasts a larger percentage of Preferred customers (30% of overall passengers carried) this segment only contributes to 43% of US’ overall revenues. A huge gap between it and its future marriage partner.

This goes back to the differences in operating strategies: while profitable, US Airways currently doesn’t need to chase after the high-paying segment to the same degree that American does, largely because it has benefited from having a lower cost base over the years. But, as mentioned earlier, such costs will rise with merger synergies, and if there is one thing that airline elitists have zero tolerance for, it is product dilution. Doug Parker cannot afford to allow the newly merged carrier to water down American’s product and elite benefits. Look no further than United, which under Jeff Smisek (who came from Continental), has seen wave after wave of elite passenger seek refuge with other airlines after growing fed up of service downgrades.

In conclusion, the task will be daunting for US Airways under Parker’s leadership: converting a quasi-LCC to a full-service legacy carrier, while still sustaining a profit. He was able to save two carriers on the brink of failure before, let’s hope he can do it again.