When I introduced the concept of fare construction, I mentioned that it involves finding both booking class inventory and also published fares, matching them together in a way that results in a complete ticket. I followed up with some suggestions of where to find airline inventory — whether for free or through paid services — and today I’ll focus on the fares.

I still believe inventory is more useful. That changes all the time, while fares are relatively static. When prices change it’s often because inventory changed. However, fare rules can also be an important factor. Advance purchase restrictions as well as higher prices for nonstop flights can be traced back to the fare rules. You can also blame them for different prices on codeshare flights.

Introducing the Fare Basis Code

The fare basis code is a string of letters and numbers that identifies each unique fare. Usually this starts with a letter that matches the booking class required to use that fare. So if your fare basis code is LA14MN, then it probably requires available inventory in the L booking class on a given flight.

There is other information in the fare basis code, but I’ll discuss that in more detail in a future post when I really get into how fare rules work. Right now just know that if you see a number in there, like “7” or “14” then that is probably also a sign of an advance booking requirement of 7 or 14 days, respectively. Beyond that most people don’t need to get too nerdy.

Why Use Fares at All?

When most people learn about supply and demand, it’s in the context of a single item that can be sold at any time. If lots of people want that item, the price is raised. If not, the price is lowered. But this view is simplistic and impractical for an airline when the seats are perishable — once the flight takes off, they’re no good to anyone.

The airline needs to set different prices for essentially the same product to segment customers by their needs and wants. They also need to take into account customers who will travel nonstop vs. make a connection. Sometimes an individual flight will be cheaper in order to combine it with other connecting flights, resulting in a higher total price and keeping all the planes full.

Fares allow the airline to separate the price of something from the available inventory. The fare includes that price as well as a set of rules that tells you how you are allowed to get between two cities. Once an airline publishes a fare, it can leave it alone for several months, set an expiration date, or even pull it early if there was a mistake. The price you pay as a customer will depend on whether you satisfy those rules and the competition for inventory on individual flights.

Where to Find Airline Fare Data

By searching for fares first you can determine the lowest possible price. Once you know the rules of that particular fare, then you can look for flights that mean those rules and also have availability in the required booking class.

A calendar search on ITA Matrix isn’t going to deliver the same results. It will tell you that one flight is cheaper than another if you travel on different dates or with a different carrier, but it won’t tell you why. You’ll be feeling around in the dark to figure out if there are other options to find an even better deal.

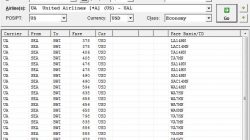

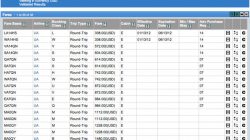

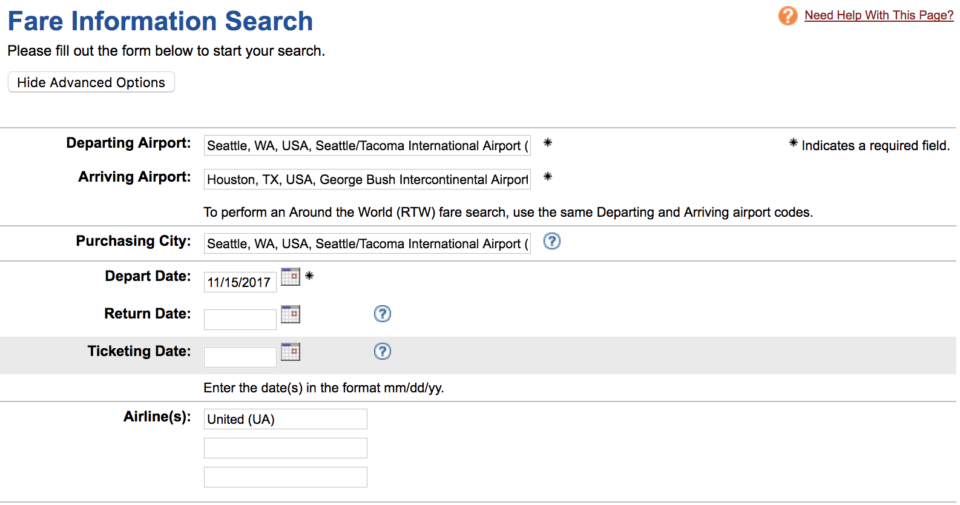

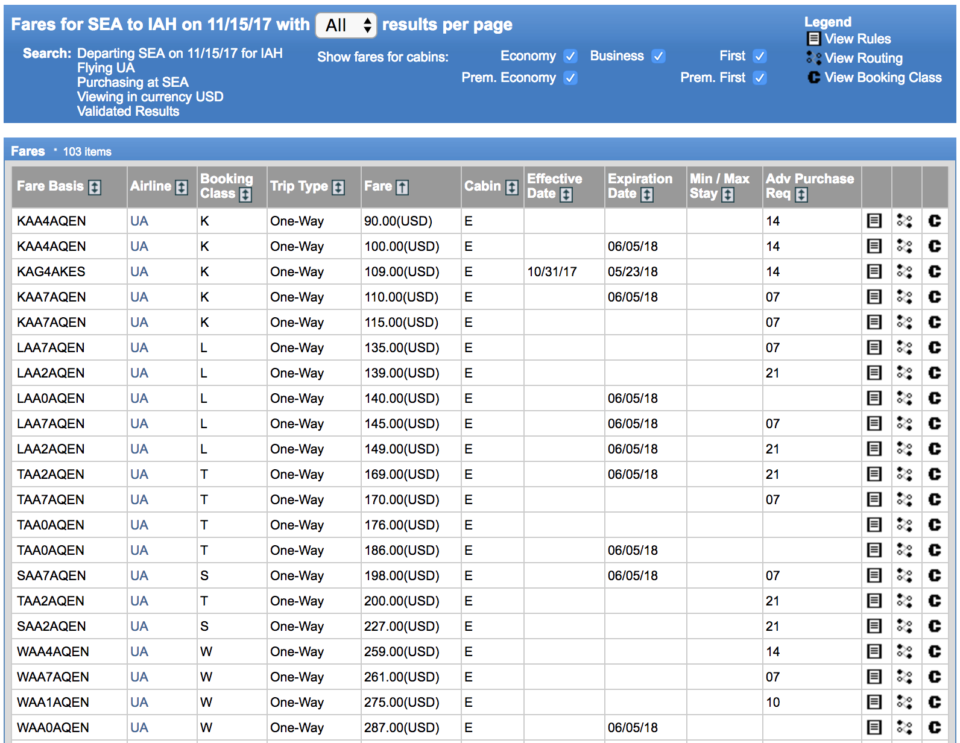

Here’s an example of a search for fares from Seattle to Houston on United Airlines that I obtained from ExpertFlyer. If you go back to my earlier post on booking class inventory, I performed a similar search, and there was inventory in nearly all booking classes on most flights.

There’s an option not shown in this image at the bottom of the search query to “validate fares.” This means that ExpertFlyer will only return results that are valid for your date of travel. It’s entirely possible that additional fares are published but cannot be used because they aren’t permitted for travel in November, or maybe just not on Wednesdays.

The results themselves are a list of fare basis codes, the airline, the booking class required to use that fare, and the fare itself (not including taxes and fees). The other columns are pretty self-explanatory; I’ll cover fare rules and routing rules later. You can even search multiple airlines at once, but in this case I wanted to limit my search to United Airlines to keep things simple.

You can see that the cheapest fare is $90 on November 19, using inventory in the K booking class and fare basis code KAA4AQEN. This means — assuming I want to fly on this day and with United Airlines — there is no possible way I can pay less than $90. I have discovered the floor, and I can use that baseline to evaluate all my options.

Notice also there are several ways the price can start to creep up. What if I wait until 10 days before departure to book my ticket? I can no longer book the $90 fare. Instead, I’ll have to book KAA7AQEN for $110, which has only a 7 day advance booking window. Maybe we’re still 14 days before departure, but the K booking class inventory is exhausted, leaving inventory in the L booking class. Now I have to resort to a $135 fare using the basis code LAA7AQEN.

Traditional airline search engines are doing all this matching automatically, but it can take some time and doesn’t show you how the sausage is made. It’s entirely possible when looking for some international flights that there will be a difference of hundreds or even thousands of dollars (for business class travel) between different fares. Then you’ll want to start digging to find out what rules you need to satisfy to make sure you can booking the cheapest flight.