I’m in the process of updating my hotel elite status comparison chart, and as part of that process I need to collect information on the different award tiers and the points earned with each stay. That allows me to do what I consider a very useful analysis of the relative cost of earning an award stay, or as I like to call it, “Revenue per Award Night.”

This measure is incredibly important when valuing any award program, but especially a hotel loyalty program. A mile is not a mile, and a point is not a point, if different programs award more or less of them for the same size transaction. As a result, one can’t easily compare the award charts of two different programs and say that one is “more expensive” than another. Perhaps the program that requires twice as many points for a free night also hands out four times as many to begin with.

Airlines have pretty standard rules for awarding miles based on distance flown and fixing the cost of a domestic award at 25,000 of those miles. These rules have been breaking down for years in a process that is now accelerating. But I can’t think of a time when hotels have ever had comparable award programs.

I’ve done this kind of analysis before, but I’ve made a few changes to my method, there have been some new award tiers added, and Club Carlson has changed their elite bonuses. The present analysis includes the following hotel loyalty programs:

- Hyatt Gold Passport

- Starwood Preferred Guest

- Hilton HHonors

- Marriott Rewards

- IHG Rewards (formerly Priority Club Rewards)

- Club Carlson

Calculating Revenue Spent per Award Night

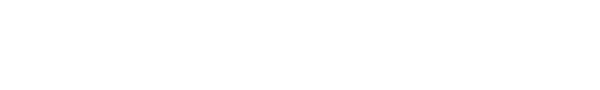

The figure below provides a general distribution of the cost of an award night. I’ve included every program’s award chart, as well as three separate award charts to account for peak or discounted awards in certain programs. I then divided the cost of a free night (in points) by the number of points earned per dollar spent when you previously stayed a hotel and paid cash.

From this first figure, we can see what I’ve shown before, that Hyatt, Hilton, and Marriott all have award charts that are similarly priced. The fact that Hilton may sometimes charge up to 95,000 points for an award night is compensated for the fact that it can offer 15 points per dollar, while Hyatt offers only 5 points per dollar. Starwood, however, has some incredibly high-priced awards among its top tiers, while IHG Rewards and Club Carlson may offer significant value even after Club Carlson’s recent devaluation.

Elite Members Spend Less to Earn Free Nights

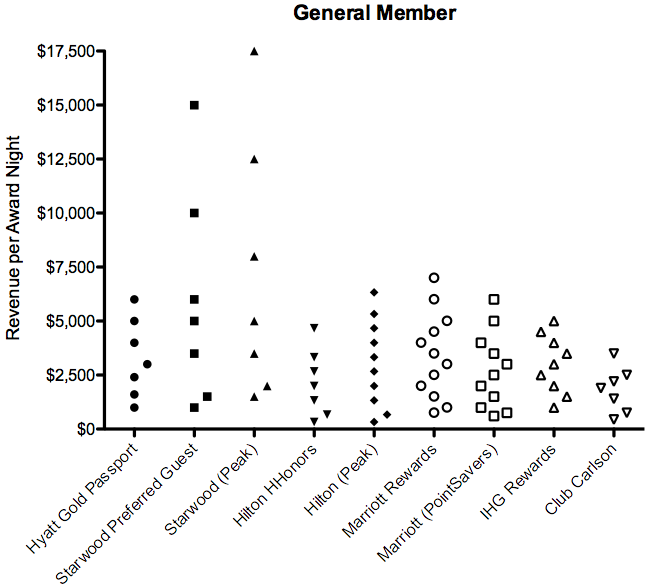

I created a second figure for elite members. Why? Each loyalty program offers its elite members a different bonus multiplier on the points they earn, which scales the “Revenue per Award Night.” So an award chart that looks unattractive to a general member could be very attractive to an elite if that elite gets a much higher bonus than some other programs provide.

For the sake of consistency, I’ve used the elite status one would earn after spending 50 nights, which includes the top tiers of Hyatt and Starwood as well as elite status several other programs typically provide for having a co-branded credit card. These are:

- Hyatt Gold Passport — Diamond (30%)

- Starwood Preferred Guest — Platinum (50%)

- Hilton HHonors — Gold (25%)

- Marriott Rewards — Gold (25%)

- IHG Rewards — Platinum (50%)

- Club Carlson — Gold (35%)

This figure doesn’t show any upsets in the ranking — every program still ranks the same when it comes to its most expensive award category. But you can see that some of the disparities are reduced. Starwood’s Category 7 is no longer roughly 3-fold more expensive than Hyatt’s Category 7; instead it’s close to 2-fold more expensive when comparing the experiences of an SPG Platinum member to a Hyatt Diamond member. And if you cut out Categories 6 and 7, SPG begins to look more attractive.

Not All Award Nights Are Equal

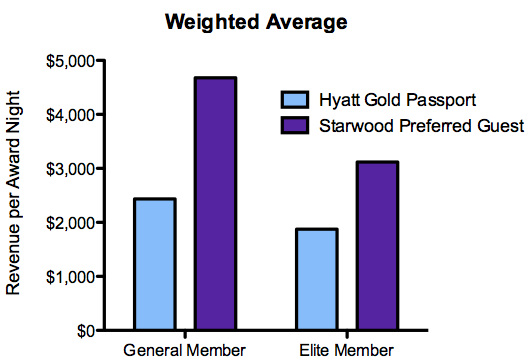

Excluding outlying categories can be appealing when they seem to skew the results, as in the case of SPG. I took out a few outliers last year from my final analysis. However, it’s not a good idea without some idea of the impact of those outliers on the greater whole.

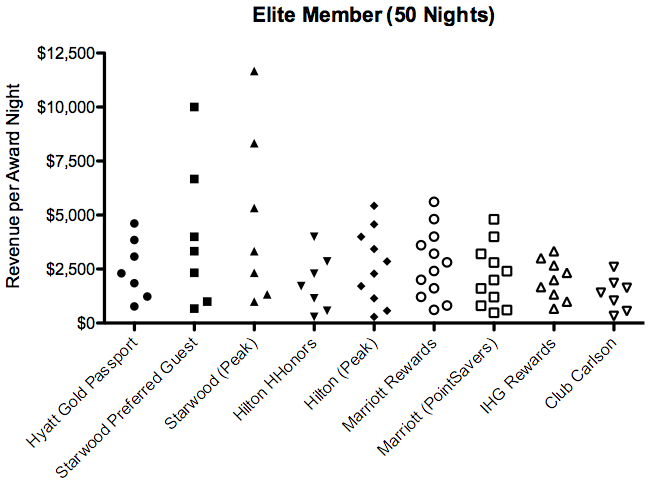

So I sat down and counted the number of properties in each award category for both Hyatt and Starwood. (I would have done the other chains, too, but Marriott, Hilton, and IHG number into the thousands. I also have status with Hyatt and Starwood, so this is for my own benefit.) The results surprised me a bit.

Hyatt exhibits a bimodal distribution centered on Categories 2 and 6, meaning they have a lot of hotels at the top or bottom of their award chart and not many in the middle. Starwood has a unimodal distribution that peaks around Categories 3 and 4. It probably explains why Starwood is able to get away with such expensive hotels at the upper end — there just aren’t that many.

Why is Hyatt split down the middle? Partly it’s because of their recent acquisitions and expansion of the Hyatt Place and Hyatt House brands. What I grew up thinking of as a luxury brand now has many more affordable budget properties — a huge number, in fact, that brings down the weighted average revenue per award night for Hyatt vs. Starwood.

They do a great job running them, and they may bring in customers that then stay at nicer hotels, but it probably creates some internal stress between two different target markets. (And when some people complain that Hyatt doesn’t have many properties — which is true — it doesn’t help the problem when most are budget-oriented.)

Another reason for the gap in Hyatt’s chart is that the top end continues to migrate further upscale. The Hyatt Credit Card gives out a free Category 4 award night each year, and it’s become more difficult to use each time category changes are announced and some favorite properties move from Category 4 to 5. We’re always hearing about fancy new properties in places like New York and Hawaii. The need for Category 7 is pretty obvious from the huge number of Category 6 properties, and I’d expect to see more of them move up in the future. We probably got off easy to start because Gold Passport was worried about customer reactions.

It’s not all bad news. An abundance of cheaper and more expensive properties makes it even easier for travel hackers to earn elite status at Hyatt at cheaper properties and benefit from that status at more expensive properties. For ordinary people, however, I think Hyatt could make a bigger effort to open mid-market hotels.

Conclusion

The first time I did this kind of analysis, I was trying to argue that Hyatt wasn’t likely to introduce a massive devaluation to its members. I said, at most, we might see some small increases in the upper tiers and the possible introduction of a Category 7. That’s very similar to what happened.

Of course, the introduction of both a Category 7 and award inflation at the same time is doubly painful, but take another look at the distribution of Hyatt properties by award category and it is clear just how few properties were affected. There remain many excellent awards at the Category 5 and 6 levels. And booking Category 7 properties with Hyatt remains less expensive than with Starwood even after considering the 20% discount Starwood provides with a fifth free night — something not everyone gets on every award stay.

There are so many nitpicky variables like these, as well as elite-qualifying award nights, upgrade benefits, and airline or credit card transfer partners that help decide which hotel loyalty program is right for you. Sometimes location matters, too. 😀 But I hope you’ve found some useful information here today that can help you make that decision. You’ll get more information once I finish creating the updated elite benefits table.

(If anyone has access to information that breaks down the number of properties by award category for the other programs, I’d love to get my hands on it. I just don’t want to count them all manually.)