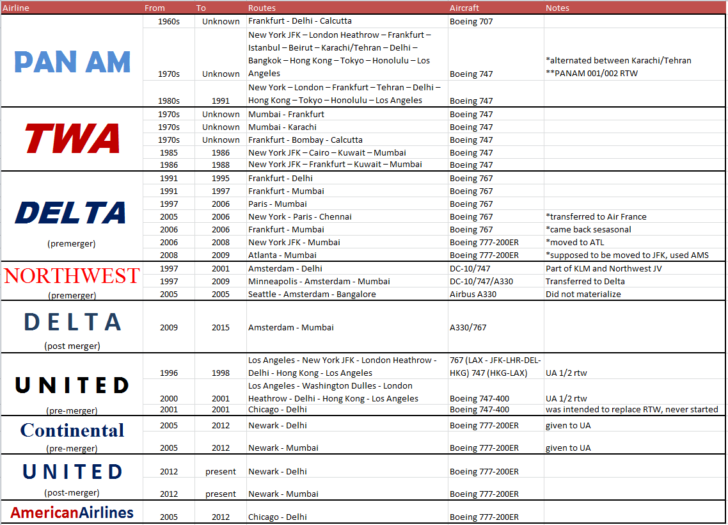

Editor’s note: this is the second installment two-part series assessing the U.S. – India passenger market and aviation strategy, and the impact of Middle East airlines carring 6th freedom traffic between the two countries. Part I, which can be found here, assessed the restoration of Indian carriers to Category I status.

Various efforts by U.S. carriers to serve the Indian market direct or nonstop have been largely a failure: today, only two routes remain from Newark to Delhi and Mumbai on United

And then there was one: Delta leaves United as the sole U.S. carrier flying to India

During the early morning hours March 28, 2015, Delta Air Lines flight 49, an Airbus A330-300, took off from Chhatrapati Shivaji International airport in Mumbai, India, at approximately 2:45 AM local time, bound for its final journey to Schiphol International airport in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

A decade ago, Delta had been the only U.S. carrier serving the India market, albeit as a 5th freedom operator from Europe rather than offering a nonstop flight from the U.S. The carrier had pulled every trick out of the hat to stay committed to the Indian market – and in the years that followed, would attempt to offer a nonstop flight from its U.S. hubs, aided by the advent of longer-range aircraft. When that venture failed, Delta settled on a daily 1-stop service that originated in New York and terminated in Mumbai via Amsterdam.

However, the morning of March 29, DL 049 went wheels down at Schiphol airport, refueled, changed crews, and continued onward across the Atlantic to JFK. Its return flight, DL 446, would make a turn at JFK and arrive back into Schiphol the following morning, but would not be making the continued journey to Mumbai as it had been doing for years.

After nearly a quarter of a century serving the Indian market, Delta would be leaving behind United Airlines as the only U.S. carrier flying to India.

Delta’s history in India dates back to the end of the Cold War

When Delta inherited Pan Am’s North Atlantic route system in 1991, it also gained a modestly-sized European hub in Frankfurt, Germany. The Berlin Wall had come down, and Delta suddenly had fifth-freedom route access to a handful of new markets in Eastern Europe, such as Athens, Bucharest, Budapest, Istanbul, Moscow, Prague, Saint Petersburg, Vienna and Warsaw, all thanks to Pan Am’s intra-European network from Frankfurt. Also included in the package were 5th-freedom rights to operate routes to Delhi and Mumbai 3-4 times per week.

Delta had also acquired route authority to operate several transatlantic routes from Frankfurt. With the ability to connect fifth-freedom traffic between markets like the U.S. and India, Turkey, Russia over Frankfurt, Delta offered 132 daily depatures at its peak period in June 1993.

But Delta struggled to turn a profit in Frankfurt, especially having to compete against Lufthansa at its primary hub. As such, the FRA operation dwindled from its 100+ peak to a mere 42 daily flights in June 1997. However, even as Delta shuttered its intra-Europe hub, and trimmed all transatlantic routes to Atlanta, Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky and New York JFK, it held onto its rights to fly to Mumbai, India. Service from Frankfurt to Delhi in 1995 became contentious given tensions between the U.S. and the Persian Gulf countries, and with increased concerns over airspace security, the route was dropped.

Nine U.S. carriers have flown to India in the past: United transitively remains after merger

As Delta continued operating to Mumbai throughout the 1990’s, other U.S. carriers came and went in the Indian market: United attempted India twice in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s with an “around-the-world” service that modeled after an approach taken by Pan Am in the 1970’s. Northwest Airlines was granted access to India in 1997 after launching a ten year joint venture agreement with KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, representing one of the first alliance tie-ups of its kind between two major network carriers. The enhanced agreement between the two airlines primarily covered all North American transatlantic routes on each others’ metal, including Canada and Mexico. However, the scope of the alliance also, for some reason, flights from Amsterdam to Delhi and Mumbai.

There was something that allured U.S. airlines to serving the Indian market. It seemed like carriers were willing to jump through huge operational, financial and regulatory hoops to operate their metal into Indian airports. Even as economic conditions deterioriated in the late 1990’s with the Asian Economic Crisis, the heat always seemed turned high.

In the early 2000’s, setbacks presented by the September 2001 attacks created a minor speedbump. United cancelled plans to launch the first U.S. to India nonstop route from Chicago O’Hare, slated to begin in October 2001.

Things appeared more optimistic in the mid-2000’s when Russia relaxed restrictions on polar airspace rights between the U.S. and Asia. After what seemed like an eternity, Continental became the first U.S. carrier to operated nonstop U.S. – India scheduled services in October 2005 between Newark and Delhi, followed shortly thereafter by American from Chicago O’Hare to Delhi. Continental later added a Newark to Mumbai nonstop in 2007.

American pulled its Chicago to Delhi flight in early 2012 after declaring that the route was highly loss-making in midst of its Chapter 11 restructuring and that yields were sub-optimal with government-owned Air India filing discounted fares on the same route pairing. United eventually assumed the two Continental routes after both airlines merged in early 2012.

After relative lack of success in attempting the U.S. to India market nonstop in the mid-2000’s, Delta was able to gain a back-door entry to India after its merger with Northwest in 2008. Delta eventually took over Northwest’s Amsterdam to Mumbai flight, and by correlation, was folded into the transatlantic JV with KLM (which had expanded to include Air France and Alitalia after KLM merged with Air France and Alitalia was included as part of an expanded agreement).

For Delta, that may have opened up greater opportunities to excel in the Indian market. But even after working through various formulas to retain access to the India , consolidation could not insulate Delta against the formidable presence of the Gulf Coast carriers, Etihad, Emirates and Qatar Airways in capturing 6th freedom traffic flows between the U.S. and India.

Delta alleges it would “fly direct to India” if it weren’t for the GCCs, which is debatable

Recently, the largest U.S. carriers, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines and United Airlines have corralled against fast-growing airlines in the Middle East, accusing the “Big Three” GCCs of receiving unfair subsidies from their respective governments in the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, allowing them to poach traffic from U.S. and European carriers.

A white paper study released last month, commissioned by Delta over a two year period, divulged that the three major Gulf carriers had recieved $39 billion in subsidies from their respective governments. Delta CEO Richard Anderson made a few brazen comments associating this with the terrorism acts of September 11, 2001 which obviously did not resound well in the global aviation stratosphere.

Still, armed with this knowledge, Delta, United and American have used this white paper study to allege that terms of Open Skies agreements between the U.S. and the Gulf region need to be re-considered given “unfair practices” as a result of the subsidies.

Using India as a lever against the Gulf carriers, U.S. airlines are now following in the wake of Germany, Canada and France in alleging that the Governments of the GCCs are poaching traffic to the subcontinent through their subsidies. The report claimed that annualized bookings by the Gulf carriers to the U.S. increased by 2.5 million over the two year period, effectively growing their market share over the U.S. – India continent from 12% to 40%, and slicing away nearly 800 bookings per day from U.S. carriers and their joint venture partners in Asia and Europe.

In early March, Delta spokesman Trevor Banstretter claimed that had it not been for the GCCs, or lack of restrictions in place to limit their growth in the U.S., Delta would be flying, “directly from Seattle to Hyderabad.” It is difficult to take this at face value given that the term, “direct” in the aviation industry can imply that a flight makes a stoppover in another market to pick up additional traffic, as Delta was already doing via Amsterdam to connect points between the U.S. and Mumbai. Furthermore, Delta’s subsidiary, Northwest, had originally reneged on plans to launch a Seattle to Hyderabad direct flight via Amsterdam in 2006, long before the growth of the Gulf carriers began to take place.

Delta is likely overcompensating for its own shortcomings in the Indian market

One of the biggest ironies of the airline industry is that global carriers will never hesitate to resort to trash talking and finger pointing, irrespective of the overall financial health of the passenger air travel market. The reality is that Delta has the capability to launch nonstop flights from Seattle to India any day if it wishes, but is not willing to admit that it could not even viably support 1-stop service to Mumbai, one of the largest U.S. – India O&D markets, from its Amsterdam hub despite enormous feed from Delta and KLM across the Atlantic.

The truth is, the U.S. is the latest country to follow in this fascination on the viability of the Indian subcontinent in the wake of Canada, Germany, Australia and other nations in years past. Of course, in contrast to those examples, there lie some key differences: for starters, the U.S. and the governments of the United Arab Emirates and Qatar have an open skies agreement, meaning as many airlines can operate as many frequencies between either country as they wish, whereas Australia, Canada and Germany have bilateral restrictions in place to the U.A.E. and Qatar. Secondly, the U.S. governments tend to be more hands-off with respect to the wide variety of national airlines headquartered in the States, whereas the Canadian government is more involved with Air Canada as well as Germany with Lufthansa.

U.S – India has been trial and error for decades. What was the excuse before the Gulf carriers existed?

The U.S. – India market has been in existence for several decades, long before the advent of the Middle East Carriers. Dating back to the glory days of aviation, U.S. carriers had presences in the Indian market – including brands that are now dead such as Braniff, TWA, Pan Am and the like. Perhaps it is more realistic to consider the dynamics of the Indian market from an economic, geographic and political perspective, and how those landscapes shift in the context of the global aviation industry, rather than claim that it is all about subsidized governments that create all of the unfairness.

Delta has re-shuffled the chairs on the deck the most out of any U.S. carrier serving India, and much of it occurred before the massive growth of the GCCs to the U.S. and Subcontinent region. Delta has attempted Frankfurt – Delhi and Paris – Madras, both of which failed. Its Mumbai flight has shifted from Frankfurt to Paris to New York JFK to Atlanta, then back to Paris, then Amsterdam.

It is highly unlikely that even without the massive presence of the GCCs in the U.S., Delta would operate a flight from Seattle to India nonstop. If a nonstop service between Mumbai and New York was not achievable, then Seattle would be even more sub-optimal given that New York to Mumbai is a much larger local market than Seattle to Hyderabad.

Perhaps it is best for U.S. carriers to realize that U.S. – India nonstop market is simply not viable

In the short weeks since Delta, as well as American and United, made their anti-Gulf resistance statements, Emirates has announced second daily frequencies to both Seattle and Boston, announced plans to up-gauge its New York JFK – Milan 5th freedom route from a 777-300ER to an Airbus A380, and also unveiled plans to launch a new route to Orlando.

It is probably better for Delta to embrace the fact that its own desires to fulfill nonstop connectivity to India is out of the realm of possibilities on a profit and loss basis.

There are multiple reasons why history has repeated itself in the U.S. to India market for decades: political, economical, geographica and technical. Unlike routes from the U.S. to countries in North Asia, Western Europe, Eastern Australia/New Zealand and West Africa, where the majority of the journey is over a body of water and/or uninhabited territories, flights to India generally overfly countries where technical fuel stops have been utilized for years. The market has always been freely accessible via stoppover points in Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

For the same reasons that few, if any, U.S. carriers provide nonstop service to cities such as Johannesburg, Nairobi, Guangzhou, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Manila, Taipei, Melbourne and Auckland, similarly, Delhi, Mumbai and the others can be easily accessed via 1-stop service through traditional hubs in Tokyo, London, Frankfurt and Hong Kong.

Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Doha have also entered into that fray, and there is nothing that the U.S. carriers can do to stop it from happening.

If anything, Delta should realize that the largest impediment to its own U.S. – India capability is not just the Gulf carriers, but also Air India and Jet Airways. If there was any national airline that has allowed the government to bail it out of consistent financial distress, it is the Maharaja.

All the while, the fact that virtually all major U.S. airlines have, in some way or another, become indebted to the U.S. government for the better part of a century to help them through cyclical downturns in the economy. The fact that virtually all of the majors have gone through Chapter 11 bankruptcy, merged/consolidated, and/or benefitted from lower fuel prices is pretty substantial. Not to mention, U.S. airlines have more or less monetized all aspects of their brand, from baggage fees to frequent flier requirements.

So, in question, why are the U.S. carriers attacking Gulf Airlines when both U.S. Indian carriers are not Boy Scouts, either?

Timing was not ideal: a lesson well-learned.

The setbacks that U.S. carriers have faced in serving the India market has been a tough pill to swallow. If one were to rewind the clock and ask any of the leadership teams among the six major U.S. carriers in 2005 – American, Delta, United, Continental, Northwest and US Airways – the interest in India was unanimous. The opportunities afforded to them when longer-range aircraft became available and when Russian authorities opened up polar routings was ideal. The timing, however, was not, when U.S. carriers realized that ultra long-haul flights were not invincible against a souring global economy, high fuel prices and a downturn in premium travel.

But to blame the failure of U.S. – India solely on the Gulf carriers is a farce that would have occurred independently of the GCCs. Certainly, they did not help, but given the fact that history has repeated itself in the context of many different changes in the global aviation sphere, its probably in Delta’s best interest to lay the hatchet and invest elsewhere.