Editors note: this is the second of two installments covering the dynamics of ultra-long haul flights that have become more and more commonplace in the global aviation world. Part one, which provided an overview and a few examples of ULH flights, can be found here. Part two assesses some of the economic and passenger experience components factored into the planning and execution of ULH flights.

Long range beauty, or long-haul headache?

Contrary to popular belief, for a global airline, the glamorous title of operating the #1 and #2 longest passenger flights in the world does not come without costs.

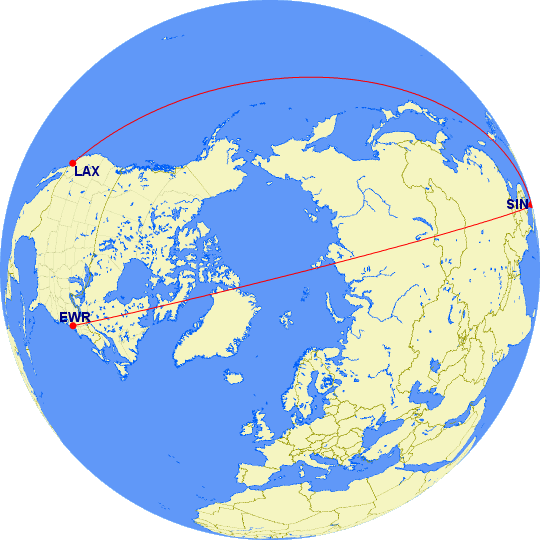

In February 2004, Singapore Airlines launched nonstop services between its home base at Singapore Changi Airport (SIN) and two points in the United States: Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) and Los Angeles International Airport (LAX).

Singapore Airlines (IATA Code: SQ) flights 21 and 22 operate SIN-EWR-SIN, each with a blocked time of 18 hours and 55 minutes heading westbound (SIN-EWR) and 17h 55min traveling eastbound (EWR-SIN). SQ 37 and 38, operating SIN-LAX-SIN, are blocked at a flying time of 17h 50min traveling westbound (SIN-LAX) and 17h 25min eastbound (LAX-SIN).

SQ launched these routes using an Airbus A340-500 series aircraft, and at present, only 5 frames of this fleet type remain with Singapore Airlines today, dedicated exclusively for use on these two ultra-long haul segments. In addition to the Boeing 777-200LR (LR=Long Range), the Airbus A340-500 is known for being an operational long haul “champion” in the global aviation world, having the capability to push back from the gate at maximum possible total weight, with the added bonus of auxiliary tanks to hold extra fuel reserves.

Still, despite the advantages of using aircraft designed with the technological advancements to fly ultra-long haul segments, the airline still has to weigh in significant cost-related decisions in order to determine break-even numbers. Many tangible and intangible considerations need to be carefully monitored closely over time in order to insure long-term viability of these flights.

One of the largest decision points involve payload restrictions, which essentially define the maximum carrying capacity of an aircraft. As is, the plane has “fixed” levels of structural weight which it needs to support, but then come the variable constraints: passenger, cargo, and extra fuel for the long journey. Fuel, of course, has the least wiggle room, given that there are legal minimal fuel requirements the tanks need to be able to meet in order to get the plane between points X and Y safely and without diversion.

However, passenger and cargo weight have a bit more mobility if the plane is exceeding its weight restrictions. In such cases, the airline then has to make the difficult decision: which will incur fewer costs to the airline, bumping freight or bumping a passenger?

Either way, it can be a nasty procedure from a customer service perspective: passengers pay expensive fares for such flights, and re-accommodation on long distance itineraries are often less convenient. Similarly, cargo, while lacking a human pulse, is still expensive, has a delivery expectation on the other end, and can be perishable.

An algebraic formula

In addition to the items listed above, the airline also has to account for a few additional pieces of the puzzle before proceeding further. Highly important is the establishing the number of crews needed to staff a 19-hour flight, and providing the necessary crew rest facilities, such as bunks, given that such routes will need an extra staff.

Next, the airline has to insure that there are enough functional lavatories that can be relied upon to service the flight. Even a single broken toilet can cause a lot of misery when out of commission on such a long journey. Furthermore, galleys need to be able to stock multiple meal and beverage carts to insure passengers are well-fed and hydrated throughout the flight.

When Singapore first launched these routes in 2004, the aircraft was designed with a mixed configuration of 117 premium economy and 64 business class seats. With 181 seats on board that provided at least some level of additional comfort above the standard coach class seat on a long-haul flight, Singapore hoped it would attract a higher-yielding passenger make up in order to break even on this high-cost operation.

However, even with decent load factors averaging in the mid-70 percentiles, Singapore still felt compelled to make some alterations, from frequency to cabin layout, in order to hit the targeted “sweet spot” and break even. Around 2007, Singapore decided to change the seating configuration from a mixed layout to an all-business class one, consisting of 100 all-business seats throughout the aircraft used on both routes. Reducing the number of extraneous economy class seats and bodies lowered the risk of hitting payload restrictions even further, while also deriving higher revenues from all-premium seats.

Grappling with uncertainty

Remodeling an entire aircraft cabin is not an inexpensive adventure, but Singapore took the plunge and hoped that the improvements would boost up the yields, especially as oil prices escalated during summer 2008.

Then came the the global economic downturn, where premium class travel worldwide took a huge hit. Singapore was forced to reduce frequencies on these routes, and desperate get passengers into seats, resorted to offering deeply discounted promotions and generous mileage redemption offers as incentives. Despite such efforts, load factors hovered below the 50% range, largely unprofitable and unsustainable in a crippled revenue environment.

2009 and 2010 were recovery periods for these flights. SIN-LAX has remained at a reduced 5-weekly schedule, while SIN-EWR has since returned to daily. Load factors have also improved; however, oil prices continue to battle against SQ’s desires towards profitability on such routes.

Demand usually isn’t the issue, either. New York and Singapore are two of the biggest financial hubs in the world, with plenty of traffic willing to pay higher fares in order to shave travel time commuting between these points.

So the question then becomes, “what is the long-term solution for Singapore?”

Keeping “the big picture” in mind

Last week, there were rumors circulating around that Singapore was “rethinking” its all-business class strategy on these two routes, and considering adding regular and premium economy seats BACK into the Airbus A340-500s. Details were fairly general about Singapore’s alleged deliberations on this business decision, however, according to an article published in AsiaOne News last week, SIA spokesman Nicholas Ionides claimed economy cabin seats, “continue to add value to the overall network offering.”

It places a certain level of scrutiny surrounding this development, particularly in light of the fact that Singapore is struggling, as is, to earn money on these routes despite high load factors in an all business class plane. If the flight wasn’t earning money when they had economy class seats beforehand, then why should they feel compelled to re-introduce them when times are even tougher?

I personally don’t work in route and network planning for a major carrier, but perhaps in this case, I’d default to believing that Singapore wants to keep the “big picture,” in mind. On one hand, perhaps these routes are simply not viable. Maybe they’d benefit from including a stop over somewhere (although that is fairly moot considering Singapore also offers a 1-stop SIN-LAX flight via Tokyo and a 1-stop SIN-JFK flight via Frankfurt on their new Airbus A380 aircraft).

On the other hand, maybe Singapore is just having to contend with the fact that these routes will be expensive to operate even if they charge fares through the roof to cover the basic costs of the trips. However, they can rest (for now) on having a strong customer base and improving load factors. Therefore, perhaps the alternative avenue they can explore right now is expanding their coverage through targeting a larger segment of fliers by adding more economy class seats. This way, they can maintain market share (and some prestige) as part of “big picture” items to keep in mind.

Cattle class…what about it?

Let’s be honest here: the majority of us are likely going to be experiencing our first ULH journey in coach class. If we were to brace ourselves for the experience, as first timers, what could we expect?

As is, the longest flight in the world *with* a coach class offering actually touches my hometown, Dallas/Ft. Worth International Airport :-). With great pride and distinction, I boast that Qantas Airways flies nonstop from Sydney, Australia to Dallas utilizing a Boeing 747-400ER (ER=Extended range) aircraft. The 8,748 mile journey is clocked at 15 hours and 20 minutes, and currently flies six times per week (although that number will rise to daily services this July).

Still, the idea of spending 15+ nonstop hours in a pressurized tube, in coach no less, can be daunting. To help quell the uncertainty, Scott McCartney, author of The Middle Seat, the air travel beat of The Wall Street Journal, published an article in January detailing the passenger experience flying aboard Qantas flight 7 from Sydney to DFW.

On a regular long-haul flight, usually one not exceeding 10 hours in duration, passengers can generally stomach a few sub-par meals, lack of a personal entertainment device, and reduced legroom, given that time flies fairly quickly. However, an extra 5 hours in middle seat 57E can add lots of additional concerns, such as dehydration from dry cabins, or the risk of blood clots from experiencing Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT).

To help mitigate these fears, the airlines generally stock up on extra liquids and frequently come through the cabin conducting, “water runs.” They also provide snacks, such as popcorn, hot chocolate and ice cream, to keep blood sugar elevated, which in turn entices passengers to get up and move about the cabin to burn off energy (and therefore lower the risk of DVT).

To infinity, and beyond…?

Over the longer course of time, as air transport continues to evolve, I doubt we’ll see any severe reductions in long-haul flying. ULH flights will likely experience slower growth than they did in the mid-to-late 2000’s (see part I for more details).

While we wait out Singapore Airlines as they study their options, I think that they do have the first mover advantage, alongside a strong track record of innovation when it comes to evaluating passenger life-cycles, to make a concrete business decision moving forward.

Further reading:

Aviation Daily: ‘The World’s Longest Flights, Part I

Wall Street Journal ‘The World’s Longest Flight, in coach‘

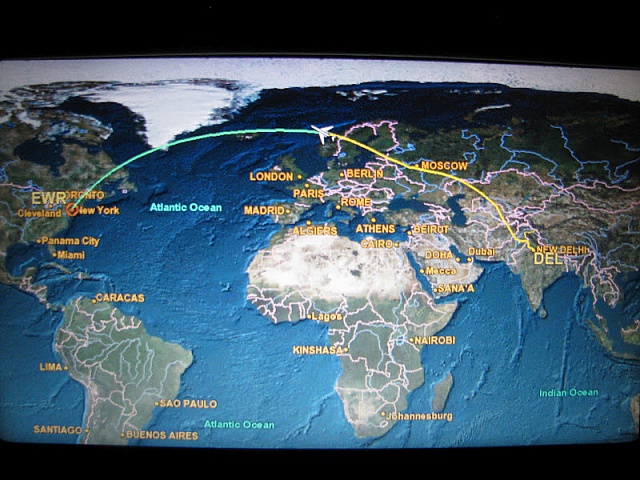

Click here to read about my personal experience on board a 14 hour + journey from Delhi to Newark in July 2010.