This is part 3 of my series on our cruise to South America in December, 2012. Today was the thing I was looking forward to second most on this cruise – making the shortest transcontinental journey in the world on our cruise ship via the Panama Canal! This was actually my second visit to the canal. The first was in December, 2005, but the ship we were on didn’t actually go through the canal. It just went through the first set of locks on the Caribbean side (the Gatun Locks) and turned around, and then we took a small boat through the rest of the canal.

For a general overview of the cruise and the trip report index, click here.

Date of Visit: Wednesday, December 12, 2012 (yes, 12/12/12)

I won’t spend a lot of time on the history of the canal itself (you can follow the link in the next paragraph for more details), but suffice to say, it is one of the world’s greatest engineering marvels, and upon its completion in 1914, revolutionized world trade by eliminating the need for ships to go around Cape Horn to get from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

When traveling from east (Caribbean Sea) to west (Pacific Ocean) through the canal, you begin at the Gatun Locks, just outside of Colon, Panama. Why the need for the locks? The canal traverses the mountains of the continental divide, which means an increase in elevation of 85 feet through the middle of the canal. Big oceangoing ships can’t negotiate the elevation by themselves, so the series of locks raises ships to the canal’s maximum elevation, and then lowers them back to sea level at the Pacific side, first through the Pedro Miguel locks, then the Miraflores locks. This site maintained by the Panamanian government has general information and illustrations on transiting the canal and the operation of the locks, along with the canal’s history and special events commemorating the 100th anniversary of the canal’s opening this year, for those who are interested.

Anyway, one big advantage we had was that our room had a balcony, so there was no need to wake up at the butt crack of dawn to jockey for position on one of the public decks (my advice – always go for the balcony if you can swing the extra cost. We woke up to this view of the jungle from our balcony, just as we were preparing to enter the Gatun locks.

As ships transit towards the lock gates, they actually aren’t under their own power. Instead, a series of locomotives pull the ship forward to the gate, where the ship waits until the lock is either filled with (when rising in elevation) or drained of (when dropping in elevation) water. This photo shows a typical example of the locomotives used in the process.

I wanted to view the canal crossing from a variety of vantage points, and I first headed to the aft (back) of the ship. It must have been my lucky day, because I actually found an open spot to view the opening and closing of the first lock (the Gatun Locks are actually three separate locks, thus rising or lowering ships in three stages). I took this short, 1 1/2-minute video of the lock gates closing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v-EX0Tk-QzU&feature=youtu.be

While waiting at the second lock, I got a view looking back towards the Caribbean sea. Here, you can clearly see the elevation change on both sides of the first lock.

I then darted over to the forward end, and amazingly, again found an empty spot to shoot photos. This is looking at the third and final lock, with Gatun Lake in the distance.

Gatun Lake was, when it was filled in 1913, the largest man-made lake in the world. Today, it remains arguably the most important part of the Panama Canal system; it is the lake which provides the water which runs the lock systems. Water is drawn from the lake to fill the last of the Gatun Locks and the Pedro Miguel Locks, and is returned the lake when water is drained from these locks. Without the lake, the canal would be unable to function. Fortunately, since the Panamanian jungle receives copious amounts of rainfall, maintaining lake levels usually isn’t a problem.

The lake is a scenic waterway, with beautiful views of the surrounding jungle and mountains everywhere.

This bridge over the Rio Chagres carries the train that we rode on the previous day.

The Rio Chagres marks the entrance to the Culebra (Gaillard) Cut, where the canal passes through the difficult terrain of the continental divide. The cut was considered the most difficult and dangerous section of canal to construct due to the terrain, made even more difficult by the relatively primitive construction technology available in 1915. These photos were taken during our last trip in 2005, but demonstrate the narrow, steep section of the cut. The bridge is the Centennial Bridge, a relatively new bridge that carries the bypass of the Pan-American Highway around Panama City.

Shortly thereafter, we approached the Pedro Miguel Locks, a single-level lock that begins the process of lowering ships back to sea level. Here, you can see a construction area where the

new, wider lock system is being built.

The amateur meteorologist in me couldn’t resist taking a couple of photos of tropical thunderstorms. This one in particular was pretty cool; if you look closely in the center of the photo, you can see the Bridge of the Americas in the far distance through the downpour.

Now on the other side of Pedro Miguel, there are clear views of the jungle to the south. We didn’t see any wildlife of significance on this trip, but on our first visit in 2005, we saw a crocodile in this general area, as shown in the second photo.

This is looking back at the Pedro Miguel Locks, with one ship waiting to enter and another leaving. You can also see here the lowered water level within the lock, which “dropped” our ship to the lower elevation on the other side.

Finally, we approached the final set of locks, the two-level Miraflores Locks on the outskirts of Panama City. At Miraflores, ships are lowered back down to sea level. This was taken from the forward end of the ship.

Being situated close to Panama City, the Miraflores Locks are something of a tourist attraction for people to come and watch ships being raised and lowered through the facility. An observation deck has been built for that purpose, and was packed with people.

Both of these photos are from the aft of the ship, looking back towards Pedro Miguel. In this one, we are sitting in the second lock, just after being lowered in. You can see the water level being raised again in the first lock to allow the ship behind us to enter.

And now, the ship is clear of both locks, and is steaming towards the open Pacific Ocean at last.

Though the distance from Gatun to Miraflores is only a little more than 40 miles, the entire transit took a little more than 8 hours. We entered to Gatun Locks a little after 8:00, and departed Miraflores a little after 4:00. The reason? Too much traffic. In fact, it isn’t unusual for cargo ships to take 20-30 hours for the entire crossing. The widening project should help to some degree.

After passing Miraflores, the Panama City skyline can be seen to the south, and the Bridge of the Americas appears forward of the ship. The bridge was opened in 1962 to connect the two sides of Panama that had been cut-off by the canal, and originally carried the Pan-American highway until the

Centennial Bridge bypass was built.

The strange looking building here is the Biomuseo, designed by architect Frank Gehry. The museum, still under construction but scheduled to

open soon, will contain exhibits about natural history of the Isthmus of Panama and the biodiversity of the area.

The condo project here was apparently partially funded by The Donald himself (Donald Trump). From what I gathered, the project failed during the 2008 recession, but the buildings still stand.

And finally, as we made the final turn to head to the open Pacific, we saw a glimpse of the marina and shopping mall we visited the day before, with the vast Panama City skyline stretching behind in the fading light of a truly awesome day.

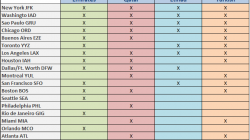

If you would like to see the canal, but cruising isn’t your thing, there are a multitude of day tours available from both Colon and Panama City to tour all or part of the canal by smaller vessel, along with shorter tours of the Miraflores Locks and Gatun Lake for ship-watching. Cruise line tours generally ran $100-150 a person back in 2012. You can probably find something a little cheaper from a local tour company. See my previous piece on Panama if you’d like more information on the country itself.