A good understanding of fare construction — including the distinction between a booking class available on a specific flight and the fare that defines the ticket’s price — can sometimes help you find and anticipate low-cost travel options.

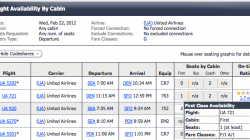

Even if you don’t have access to all of this information (a paid service like ExpertFlyer or KVS Tool can help), the basic details are provided for free when you use a search engine like ITA Matrix. That should give you a sense of whether you’re getting the best possible deal.

Booking Class Is Not Cabin Class

Before we get started you need to know that “fare class” or “booking class” is entirely different from “cabin class.” The cabin class is the class of service you can expect on the plane, whether first, business, or economy.

The booking class is a letter in a hierarchy, and multiple booking classes are available in each cabin. Each booking class must be paired with a published fare that contains the rules for how you may travel between cities and the price of the ticket.

Frequently there will be some correlation between booking class and cabin class. If your fare class is F, then that always means first class. Similarly, Y always means coach or economy class. However, some airlines have rules that allow a Y fare to get an instant upgrade (with conditions) to first or business class.

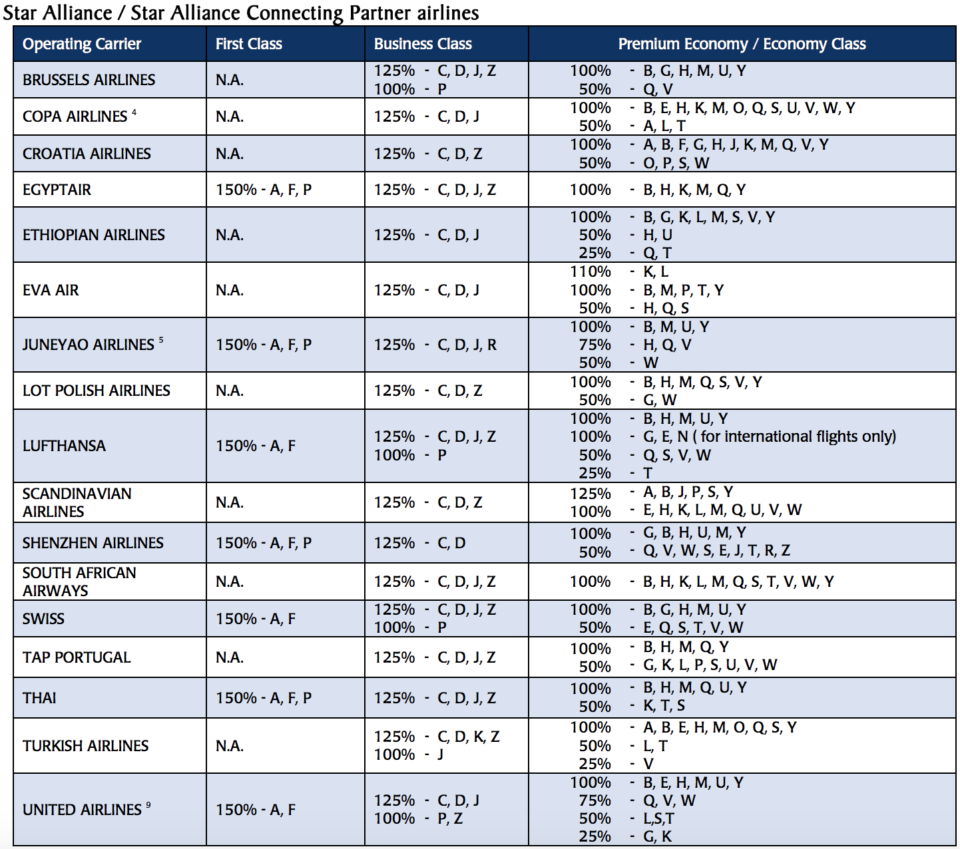

The breakdown of fare classes looks something like this example from Singapore Airlines, which shows how many miles you’ll earn on Star Alliance partners like United Airlines.

There is a lot of variation in the letters used for discounted booking classes within each cabin, and they are certainly not alphabetical. If you want to know the exact hierarchy for a given airline, that information is usually available on its website.

Ticket Prices Change in Predictable Ways

You must be shaking your head. Really? Yes, really. There’s a method to this madness, and it doesn’t involve checking on a Tuesday afternoon because that’s what you heard on some big news site. In fact, there are three common ways the price of a ticket can change for very sensible reasons:

- If a given booking class runs out of inventory, you might need to choose a different one that is associated with a different fare.

- If you cannot meet the rules of a fare (such as an advance booking requirement), you might need to choose a different booking class associated with a different fare.

- If a new fare is published, the same booking class might be available, but now it’s associated with different rules and prices.

Knowing this, if you see that a particular booking class is running low or that a fare will expire in a few days, you can anticipate that the price of a ticket will also change. However, sometimes fares and booking class inventory will change without warning, so you cannot assume that anything is guaranteed. One of the common ways that airlines fix a mistake fare is by emptying the required booking class. The fare itself can persist for a few hours longer, but it will be impossible to book.

Overlapping Booking Classes

Booking classes (or fare classes) are sometimes referred to as “buckets.” But this is misleading because the buckets are connected to each other. Emptying one bucket might — or might not — affect the inventory remaining in another bucket.

A better way to imagine booking class inventory is like a game of Jenga or a house of cards. It’s easy to take off blocks from the top of the pile, but removing them from the bottom of the pile will probably affect those above.

For example, there might be seven seats left on an aircraft. Any of those seats can be booked using the most expensive, full-fare booking class, so Y = 7. But maybe only some can be booked with the less expensive, discounted booking class, so N = 2. Imagine someone books two tickets in N. Now N = 0 and Y = 5. But if someone books two tickets in Y, then N = 2.

Overselling Inventory

Airlines also know that some people, for whatever reason, do not show up for their flight. Even if there are only seven seats left on the plane, the airline might load enough inventory so that Y = 9. Statistical models give it a good estimate that two people won’t show, and rather than let those seats leave empty it will try to sell them to someone else.

Two seats are essentially sold twice. The airline just doesn’t know until departure which person is actually going to sit in it. Along with all the different booking classes, this practice of overselling helps the airline maximize revenue AND lower prices for the rest of the customers.

How to Use Airline Inventory to Find Cheaper Flights

Essentially you are competing against other passengers, who might buy up the cheap inventory, and the system, which might determine that the cheap inventory is no longer eligible to be sold. There are also small changes in availability performed by the inventory management department at the airline.

Your best bet if you find a ticket price you like and aren’t ready to buy is to figure out what booking class it uses, the associated rules, and how many of those tickets are left. Then you can make a reasonable estimate of how much time you have left and how likely it is to sell out before you make up your mind.

When you see a warning on a website that “two tickets are left” at this price, that’s usually the amount of remaining inventory in that booking class. But you can check this for any ticket even with no such warning. Try repeating your search with a request for more and more tickets to see when the price goes up. Or you can use a paid service like ExpertFlyer to look up the number very easily.

Trying to determine the fare rules is much harder to do for free. Often a one-, two-, or three-week advance purchase window is common, especially for domestic tickets. I suggest checking for flights leaving on earlier dates and finding what date (and thus the advance purchase window) causes the price to go up. Again, ExpertFlyer will provide this more easily. I’ll be providing more detail on where to find this information and how to match inventory with fare rules in future posts.