Over the past year, US airports have gotten way more aggressive about policing Uber and Lyft pickups and drop-offs. Airports around the country, ranging from Los Angeles (LAX) to Boston have implemented sweeping changes to the policy for ridesharing apps like Uber and Lyft, which usually takes the form of moving pickups (and sometimes dropoffs) to a standardized, centralized location. At LAX, arriving passengers will have to catch a shuttle from one of the terminals to a new lot located to the east of Terminal 1. Uber and Lyft will be banned from picking up passengers curbside at any of the terminals starting this Tuesday, October 29.

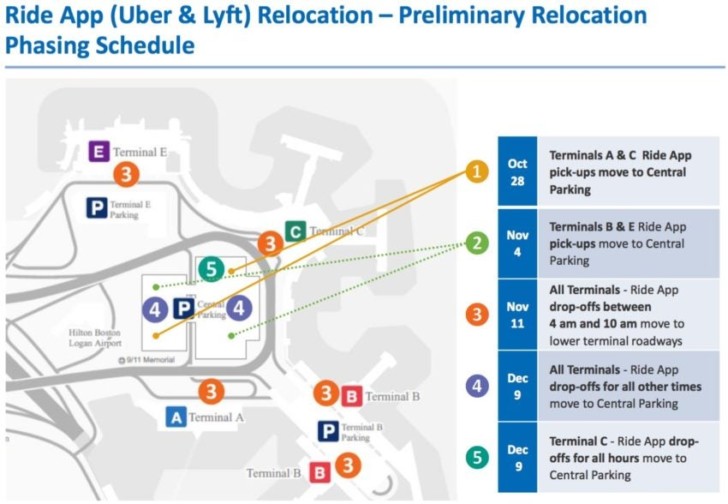

Meanwhile at Boston Logan, passengers will have to walk to a new location in the central parking garage in a phased rollout. The change will begin rolling out on Monday, October 28 for passengers arriving at Terminals A (housing Delta and WestJet) and C (housing JetBlue and Cape Air). Passenger pickup for Terminals B (United, American, Spirit, Alaska, Southwest) and E (international airlines and all international arrivals) will move to Central Parking. Then, beginning December 9th, passenger drop off (except between 4:00 am and 10:00 am) will move to Central Parking as well.

The justification for this move at virtually every airport that has made it usually boils down to reducing congestion for airport access roads, particularly in the arrivals zone. Airport access roads, particularly at large hub airports, have grown substantially more congested in the past decade. And I am actually sympathetic to this argument. LAX has been hellacious for both passenger pickup and drop-off at peak times in the last couple of years, as have San Francisco and Boston at certain terminals (mainly Terminals C and E). Many of these airports simply do not have adequate landside infrastructure for their current volume of passenger traffic.

But merely banning Uber and Lyft from the terminal access roads is not an adequate solution. In fact, I would argue that it’s a capricious and poorly thought out response to the (very real) problem that I laid out above.

Uber and Lyft Aren’t The Primary Drivers of Increased Congestion at These Airports

The first problem I have with this move is the chain of logic itself. Uber and Lyft have certainly accounted for an increasing share of airport drop offs and pickups, but the primary driver of increased congestion has actually been private vehicles. Let’s take the example of LAX and use some back of the envelope math. According to Los Angeles World Airports, approximately 28.8% of arriving and departing passengers used LAX in August 2019. But private vehicles accounted for 55%. Let’s be generous to LAWA and assume for a second that this market share has been constant since 2009. In that same period, passenger traffic at LAX has grown from 56.5 million to 87.5 million. Pulling out the ~20% of LAX passengers that are connecting, that implies a jump of ~24.8 million departing and arriving passengers. If we use LAWA’s August 2019 market share figures (which actually overstate their case), there have been an extra 7.8 million Uber and Lyft rides to and from LAX since 2009. But there have been 13.8 million extra private vehicle trips in the same period. Private vehicles have contributed at least twice as much to the extra congestion at LAX as Uber and Lyft.

Private Vehicles Are Worse for Congestion than Uber and Lyft

Yet despite the statistic above, people (and certainly politicians) are conditioned to treat Uber and Lyft as distinct from and somehow worse for congestion than private vehicles and taxis. Yet the exact opposite is true. Private vehicles, by their very nature are more difficult to coordinate time wise. Just think about how many times you’ve had a flight that is 20 minutes late because you were waiting for a gate or because you had to circle the airfield a couple of times. Unless you do a really good job of coordinating times, a non-trivial portion of private vehicle passenger pickup ends up with the person picking you up either taking up space in airport arrivals or circling around the terminal access roads (which doesn’t help congestion).

In contrast, because Uber and Lyft are ordered on demand, they contribute less to congestion on average for passenger pickup. For passenger drop-off, the gap is much shorter, but even there the need for hugs and goodbyes probably adds an extra minute or two on average. Taxis are also not any more efficient. While taxis are usually forced into a queue, whether a passenger is taking a taxi or an Uber, that is still one extra private vehicle on the terminal access roads.

There is no good reason to treat Uber and Lyft differently than any other low occupancy vehicle at airports.

Most People Taking Rideshare Would Not Switch to Public Transit

One group cheerleading these moves are environmentalists and public transit advocates, who seem to believe that making the Uber and Lyft experience at airports worse will magically encourage more people to use public transit. And if the conditions supported it, I would be happy if this happened. I am not an anti-public transit bigot. When I’m traveling to other developed countries in Europe and Asia, I almost exclusively use public transit. I’ve taken more than 10 roundtrip journeys on the Heathrow Express, and will gladly use the train or even bus where it makes sense.

But at the US airports where this move is being made, it’s simply unrealistic to think that passengers will shift to public transit. In fact it’s more likely that they would switch to taxis or private vehicles, which would be likely to worsen congestion. At most US airports, the fundamental problem is that the airports do not have a functional rail option, and instead rely on buses as their public transit. Taking the train, with its guaranteed timings and the ability to avoid traffic. Buses on the other hand have to sit through the same traffic as single occupancy vehicles. If I’m going to be stuck in traffic anyway, I’d much rather do it in a car or taxi than in a bus, which is likely to drop me off several miles from where I need to be anyway.

That brings us to the second problem – taking public transit from most US airports creates a major last-mile problem (or in the case of LAX last thirty mile problem). American cities are simply not configured around effective public transit systems. So even if I could somehow be convinced to take a bus (or train) to downtown LA, that doesn’t do me a lot of good if my final destination is in Hollywood or Santa Monica, let alone Orange County. This isn’t true at every US airport; a direct train from the airport(s) to downtown would work really well in New York, Washington DC, and Boston. But in the vast majority of US cities, the public transit system writ large is not an effective substitute for a private vehicle.

Going After Uber and Lyft Is a Way For Politicians To Avoid Making Hard Choices

None of the above is meant to downplay the very real challenge posed by landside congestion at US airports. There are real underlying issues here, and thinking about smart solutions would be welcome. But the current policy approach mostly serves as an easy way for local politicians to look like they’re doing something while avoiding the underlying issues entirely. In the cities where these policies are implemented, the mostly progressive voter bases are already inclined towards misplaced anger at Uber and Lyft for a variety of reasons that have nothing to do with airports. So this move will tend to be politically popular, even if does nothing to solve congestion.

There are hard choices that politicians and governments could make, whether that’s expanding landside infrastructure or making public transit viable. For example in Boston, the current Silver Line could be given a dedicated lane during peak transit period (perhaps shared with other buses like the Logan Express). That might actually convince a large number of passengers to switch to public transit. But wealthy suburban commuters and Bostonians would throw a fit. So instead we get this half measure, and it’s somehow presented as a meaningful solution.

The current trend in US airport policy towards Uber and Lyft may sound appealing, but in practice, it is unfair and unlikely to meaningfully affect congestion.