Many hotels aren’t owned by the brand — they’re independently owned franchises that contract to display the brand’s “flag.” The brand establishes certain standards that can be incredibly detailed while also taking a cut of the hotel’s revenue in exchange for marketing. That marketing includes loyalty programs and the points that you earn with them.

It’s an arrangement that works pretty well sometimes. On an upcoming trip to Spain, I immediately searched for and booked Starwood hotels. Though I will glance at a few other brands or even independent operators, I don’t normally give them serious consideration. It takes a lot of stays with one hotel to get a reputation as a regular. Staying occasionally with each of several different hotels that are part of the same program will earn you recognition a lot faster. (A less personal, corporate-ized version, but still recognition.)

That can be great news for the member hotel if I’m paying cash for the stay. Loyalty to its sister properties led me to do business with them even if I’ve never stayed at that specific hotel before. Award stays also provide some income, but not nearly as much. That tradeoff explains why award availability can sometimes be difficult to find — no one gives anything away for “free” if they can help it.

Two Awards & Two Very Different Types of Compensation

Award nights are generally grouped into two types: “free night awards” and “points and cash awards.” The free nights are the ones paid for entirely with points, and many programs have a published policy that they are available without blackout dates as long as a standard room is still for sale. Points and cash awards allow you to pay partly with points and partly with cash. They can be a great way to stretch your points further, but availability of these awards is up to the discretion of the hotel.

Why the different rules for availability? It has to do with the compensation hotels receive from the loyalty program for letting you book that award.

Free Night Awards

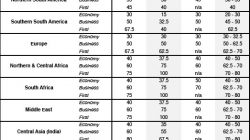

Loyalty programs are part of any brand’s marketing expenses. The marketing expenses cover the points that you earn on each reservation, and later the hotel may get money back when customers redeem points. It’s not the same money from the same person, but on average it’s supposed to work out. The catch is that the money the hotel gets depends a great deal on occupancy.

Free night awards pay off well when the hotel is full but poorly when the hotel is empty. This makes sense. If the hotel has to offer standard rooms for awards whenever they’re available, there is a great deal of potential revenue at stake as it begins to sell out. If the hotel remains empty, the theory is they wouldn’t have sold it anyway, so only modest compensation for staff and upkeep is necessary.

Each night a hotel will calculate its occupancy and submit a report that determines how much it gets paid for any awards booked. Go above 95% occupancy and it may get 95% of its “average daily rate” (ADR) for each award room. If the award night cost the guest 40,000 points and the ADR is calculated at $375, that would be worth $356.25 to the hotel. Not bad. Remember the ADR is an average, so this person redeeming a free night could still be one of the more profitable guests.

But if occupancy drops below 95% then the hotel gets another, fixed value. This can range from $25 to over $400. For an ADR of $375, that fixed reimbursement is $200. What a difference!

Points and Cash Awards

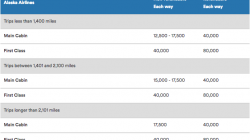

Points and cash awards offer a compromise. The hotel gets a lump some of cash from the guest, say $125, and the program provides an additional payment based on the number of points. For example, the points portion may be reimbursed at a fixed rate of 0.5 cents per point, so 20,000 points are worth only $100. Now the hotel gets $225 per night for each points and cash award. Occupancy has nothing to do with it.

Note that some points and cash awards operate differently. IHG Rewards, for example, is effectively selling some of the points required at a fixed rate regardless of the property and then books a normal award for you. If you later cancel the award, you get all the points back.

Points and cash awards can be a great deal if the hotel expects to be below the occupancy threshold because it means more money. The guest may also like to take advantage of it. Imagine the published rate is $375, and I’m offered a choice between 40,000 points for a free night or $125 + 20,000 points for a points and cash award. I’ll pay just 33% of the room rate but save 50% of my points!

But remember the hotel can decide how many of these awards it wants to make available. If it expects to be full, free night awards are a better deal because they pay out at ~$350, over 50% more than the cash and points award.

Summary Advice

My experience is that popular hotels don’t offer points and cash awards even when there are plenty of rooms for sale. But free night awards are still available because (1) the hotel is required to offer them and (2) it expects to receive more generous compensation for them when it eventually sells out. When ranking availability, we can thus say that points and cash awards will be equally or less plentiful than free night awards.

How can you book points and cash awards at the most popular hotels that prefer not to offer them? Like free night awards, they will be most plentiful when you book far in advance, but for a different reason. Free night awards are available far in advance because the hotel isn’t sold out yet. It has to provide those awards. Points and cash awards are available far in advance because the hotel can’t predict it’s inventory. This may have more to do with seasonality. I can guarantee you that some tropical destinations are going to be popular during the winter holidays. If I were the hotel’s manager, I would never provide a points and cash award during that holiday week — even a year in advance — because I expect to sell out eventually.

This doesn’t have to be as depressing as it sounds. Remember that a points and cash award can still be more profitable than a free night award if occupancy falls below 90-95%, and many hotels have worse occupancy rates than that. The key is not to travel during periods of exceptional demand.

A final factor that comes into play is how closely the hotel’s room rates tracks its award category. Remember that reimbursement for a points and cash award often includes a fixed amount for the points, so a higher category means more points and thus better reimbursement. If the hotel is in an artificially high award category (or if the entire program is designed to minimize value opportunities for the consumer) then the hotel may find that awards don’t represent much discounting at all and will have less motivation to hold them back.