I provided some support for the institution of elite qualifying dollars a few weeks ago, arguing that — independent of any revenue objective on the airline’s part — they encourage the customer to focus on booking an itinerary that meets his or her ideal conditions for comfort, convenience, and service. Rather than focus on absurd routings or upgrade strategies, customers who pay for the trip they want are more likely to have their expectations satisfied.

But I also said that I don’t think elite qualifying dollars are necessarily the best way to determine elite status on a loyalty program.

If an airline awards status purely on the basis of miles, as in the past for many carriers and the way a few continue to run their operations, then sure, it’ll attract some people who are probably costing the company more in benefits than they pay in. I think it’s still a good way to measure loyalty because these are people who are going out of their way to fly that carrier vs. more direct or cheaper itineraries.

If an airline awards status purely on the basis of how much they spend (elite qualifying dollars or some other dollar-based tier points) then it will end up with people who may pay a lot because they book at the last minute and are seeking a convenient itinerary — not because they’re loyal. It’s a great way to reward your best customers but isn’t necessarily a way to influence their purchasing behavior.

Introducing both elite qualifying miles and elite qualifying dollars as deciding factors seems like an effort to merge the best of each approach. The airline will get loyal travelers who fly further despite the inconvenience and also spend a lot of money.

The problem is that such a system measures each factor separately. A person may be flying a lot and spending a lot, and it still doesn’t mean that customer is actually providing the carrier sufficient profit on individual flights. Some flights will be “loss leaders” and others will be highly profitable. Sure, it could work out on average. At the same time, perhaps some unique customer will be booking flights — purely by accident — where the carrier is always operating on the edge and never earns a sizable profit even as the customer meets both requirements for elite status.

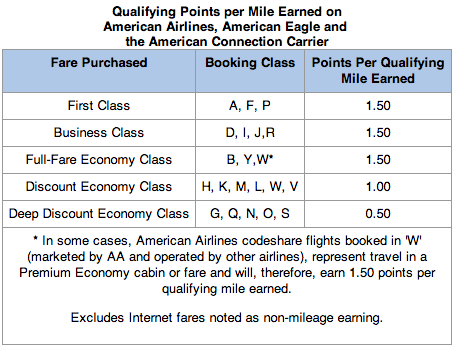

I think a better model for awarding elite status may be similar to American Airlines’ elite qualifying points (EQPs). These are tracked separately from elite qualifying miles (EQMs) and use a fare multiplier to award more or fewer miles than those actually flown.

Is this the same as the bonus EQMs that United, Delta, and other carriers still use? Not quite. Those carriers almost always provide 100% elite qualifying miles on every route. A fare class bonus can raise that number but doesn’t have the necessary range to accurately reflect huge differences in fares. Someone in first class may be paying 500% or 1,000% more, yet the airline wants to award him a measly 50% bonus? United introduced a new N fare class last year that is even lower than the G fare class, and yet it still provides 100% award and elite qualifying miles.

The problem is that carriers are awarding bonuses for full fares, but they’re not penalizing people for buying deeply discounted fares.

When American tracks EQPs, a customer may earn as few as 50% points for the cheapest fares, 100% for the middle fares, and 150% for full fares — this is a three-fold difference and may still not be enough. Many foreign airlines go to further extremes.

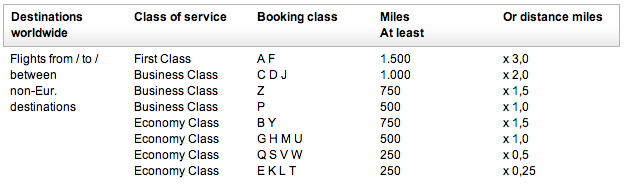

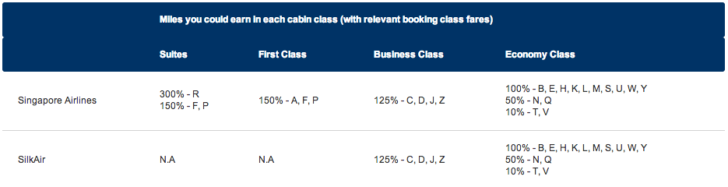

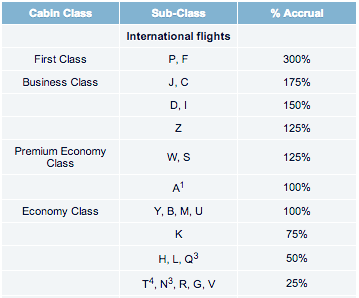

Just take a look at all the routes and fares that earn 50% and sometimes only 10-25% — even when flying on the same carrier. On the flip side, premium fares can earn 300% of the miles flown, far higher than the 150% limit seen among most domestic carriers. Check out these examples from Lufthansa’s Miles & More, Singapore’s KrisFlyer, and Air France’s Flying Blue. The difference in accruing elite status between the cheapest and most expensive Singapore Airlines fares is a factor of 30. On Lufthansa and Air France, it’s 12. On American, it’s 3. On United, it’s just 1.5.

Such a system is simpler than tracking elite qualifying miles and elite qualifying dollars separately. Airlines don’t have to develop the necessary IT to track all the different sources of revenue a customer generates through direct purchases, bulk ticket sales, codeshare revenue, and ancillary revenue. It reduces the problem of people who try to earn status based only on how far they fly or how much they spend and refocuses it on how profitable that person was in each transaction.

Customers can still be rewarded for booking cheap fares and filling up empty seats far in advance, but they will give up elite qualifying points in exchange for the discount. Others who book at the last minute will still have a reason to choose less convenient routings that travel farther vs. competitor’s nonstop flights — combine the full-fare multiplier with a longer distance and they’ll be rewarded for both revenue and loyalty.

So will American Airlines switch to a revenue model like Delta, or will it at least adopt elite qualifying dollars like Delta and United? I hope not, and I don’t think they have to. Their existing elite qualifying point system is probably sufficient — or would be with refinements. I believe they could achieve similar goals as their competitors, while linking elite status to profitability rather than revenue, by eliminating traditional elite qualifying miles and focusing entirely on points.